Index Of Social And Economic Well-being Shows Scotland Dropping Down The Table

22nd January 2020

Scotland has experienced a fall of five places in the Index of Social and Economic Well-being (ISEW) of 32 OECD countries and a drop of 0.05 between 2006 and 2018. This is according to the latest report from Scottish Trends.

The document, produced by economist John McLaren, of the Scottish Trends website, also noted life expectancy remains the weakest area of performance for the country, standing at around 79 years old.

However, in relation to Scotland's performance it is possible to identify some clear challenges and potential policy prescriptions to improve matters.

On GDP per capita With the decline in North Sea related income having halted for now, concerns turn to the underlying strength of the onshore economy. Private sector services in Scotland have seen poor growth rates in recent years, even after taking into account any impact relating to the decline in North Sea activity. However, the causes of this are little understood as the area is under-researched.

As with the UK, on-going low growth in productivity is a major concern but one where the role and ability of government to improve matters is debatable. Rather, private sector business and investment decisions, many of which are made outside of Scotland itself, will be the driving force for change, good or bad. These decisions in turn will continue to be affected by on-going political

and economic uncertainty surrounding Brexit and independence.

In terms of government policy, finding concrete ways to complement private sector activity in areas like tourism and green energy would be welcome, as opposed to the pursuit of poorly designed productivity targets.

On education

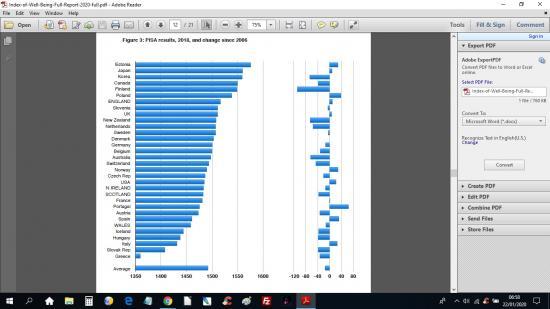

Scotland's declining PISA score is a worry that has already prompted change but not necessarily for the good. The introduction of the Curriculum for Excellence (CfE) looks increasingly like a failed experiment. However, it is difficult to judge on this matter due to the lack of robust data by which education standards can be properly measured. This poor evidential basis was highlighted by the recently re-convened Commission on School Reform.

The question remains as to whether CfE should be completely abandoned and a new strategy implemented or whether it can be adapted without the need for more disruption and upheaval.

What does seem clear is that simply paying lip service to lessons taken from OECD and others on good education policy will not deliver higher standards. Instead, PISA findings over the importance

of the quality and independence of teachers and schools and of preferred teaching practices need to be implemented in a more meaningful way and bearing in mind the specific historical and

cultural context existing in Scotland.

Looking south of the border could help Scottish policymakers to identify good practice for improving school performance. There have been so many initiatives in the English school system over the past twenty years that it can be difficult to know what has worked and what has not.

Nevertheless the fact that England's PISA performance has not fallen, on average, and that the performance of some areas, in particular London, have improved notably should provide food for

thought and for moving forward from the disappointment of CfE.

On life expectancy Scotland continues to rank lowly and is failing to catch up.

It may be that more emphasis needs to be put on longer term measures for future generations. In particular more money being spent on early years interventions and on preventative health

measures. While the Scottish government has boosted funding for both in recent years it has not done so to the degree that is likely to make a decisive difference. On early years in particular the evidence strongly points to the need for high quality care, as opposed to simply provision of facilities and sufficient staffing.

While successive Scottish Governments have made positive interventions with regards to curtailing bad habits (e.g. over cigarette and alcohol consumption) more needs to be done, as the recent rise in the number of smokers and adolescent drinkers suggests. New forms of incentives and disincentives may need to be introduced, as an alternative to largely financial based ones.

What does seem to be true is that, post Devolution, the wide array of measures put into place to improve health practices and behaviour has had little impact on Scotland's relatively poor

international performance on this measure.

Looking across the OECD, the rise in Estonia's life expectancy stands out, and more work might be done to gain an understanding of how it came about.

On the employment rate

The rise in the employment rate since 2006, given the poor economic circumstances post 2008, has been a welcome surprise. The future challenge is over how to keep the employment rate at

such a historically high level while at the same time improving the rate of growth of productivity and the quality of jobs created.

Successive rises in the minimum wage do not appear to have had much, or any, negative impact on employment. Another challenge therefore is how to keep improving the conditions of the low

paid while retaining them in employment.

Overall, given Scotland's current placing, gains in this area are likely to be more modest than in any of the other three measures.

Explanations of underperformance and barriers to future improvement Post devolution, Scotland appears to have underperformed policy wise, in particular in relation to health and education. What might have contributed to this underperformance?

Some causes seem clear:

- There is a lack of being held to account over policy decisions, in other words too little scrutiny

and proper evaluation of the actions of the Scottish Government. This is down to a variety of shortcomings, including: a weak Committee system in the Parliament; a lack of academic

involvement; a dearth of think tanks; poorly funded political parties; and a declining and underfunded media presence.

- The policy development and evaluation landscape is very weak. For example, few think tanks exist and those that do are mostly poorly funded by either the public or private sectors. For example, at the UK level, the health system is analysed and held to account by a mixture of the IFS, the Nuffield Trust, the Kings Fund and a variety of other independent bodies. However, all of these bodies concentrate on the English health system and do little in the way of analysis of any of the devolved health systems. This leads to a lack of new policy development and a lack of existing policy evaluation. At the UK/English level much of this think-tank funding comes from

the private sector. However, in Scotland there is next to nil private sector involvement in any activity that impinges on the Scottish Parliament or government policy making.

- Outside of the SNP, Scotland's political parties are either small operations or effectively branch operations of UK parties and in both cases poorly funded. This has inhibited the development of

alternative policy ideas and led to a lack of political competition, as their operations are relatively ineffectual in challenging the well funded and civil service supported (in technical terms) SNP led

government.

What the above criticism amounts to is the lack of helpful supporting bodies in the Scottish political system that, in normal circumstances, would complement the Scottish Parliament, especially in relation to policy development and evaluation. This may have been understandable initially but, twenty years into devolution, is becoming more of a handicap to progress.

How might things improve?

- Overhaul the current Committee system within the Parliament to ensure greater independence from the government, or introduce some form of bicameralism into the Parliament.

- Encourage greater private sector support for independent think tanks, not just economic but also in relation to health and education. This is more likely to come about if interested private sector

companies are confident that their involvement will not have potential negative side effects in terms of their relationship with the Scottish Government.

- Undertake a review of public funding for political parties which seeks to ensure at least base funding in order for political parties to formulate their own, evidence based, policy program for Scotland. This need not preclude some political parties being better funded than others, through private contributions, but would at least allow for more effective opposition, which is generally recognised as a healthy state of affairs in any Parliament.

At present, given the domination of constitutional events, it seems highly unlikely that any such changes are imminent.

Conclusions

Looking beyond GDP as a measure of success is an increasingly popular way for governments to assess their performance. Indeed the Scottish Government itself is committed to introducing wellbeing as a key aspect of budget decision making.

The Index of Social and Economic Well-being (ISEW) analysed here is therefore an interesting guide as to how devolved UK governments are performing across a wider range of economic and

social goals. In the case of Scotland, the results are worrying, in particular the decline in its education standing and the lack of improvement in life expectancy.

While the overall results shown here should not be interpreted as an argument against devolution, it does highlight that greater political devolution alone does not easily lead to an improvement in

key policy areas. More informed, and better evaluated, policy choices are more likely to bring about such improvement. Currently, for the reasons outlined above, this does not appear to be

happening.

It will be interesting to see if next months Scottish Budget, with its greater emphasis on well-being, is more radical than past efforts in redirecting money towards preventative rather than treatment

based measures, especially in relation to health and education.

The example of New Zealand, probably the world leader in this new type of budget prioritising, may be telling here. Its emphasis on mental health and child well-being has led to both areas receiving

very considerable boosts to funding in the first well-being led budget of 2019.

At present, the willingness across the Scottish Parliament to be equally radical seems thin on the ground but, without it, improvements in key aspects of the quality of life may fail to emerge over the next twenty years of devolution.

Read the full report at http://scottishtrends.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/Index-of-Well-Being-Full-Report-2020-full.pdf

About John McLaren

Independent economist at Scottish Trends. Previously worked at Fiscal Affairs Scotland, H.M. Treasury and at the Scottish Office. Honorary Professor of Public Policy at the Adam Smith Business School, Glasgow University.

John McLaren also writes at http://sceptical.scot/author/john-mclaren/