Public Sector Finances: February 2020

21st March 2020

From the Office for Budget Resposibility.

Government records a small deficit in February, but coronavirus will see borrowing rise dramatically.

The public sector recorded a modest budget deficit in February, a £0.3 billion improvement on last year, largely reflecting timing effects that depressed public spending. But the data have yet

to reflect the spread of the coronavirus in any significant way. In coming months the resulting disruption of economic activity and the policy measures taken by the Government and the Bank of

England will increase public sector borrowing and debt significantly.

Headlines

The impact of the coronavirus crisis and the Government's response to it on tax revenues and public spending will only feed through fully to the public finances data with a lag, both because

initial outturn data are partly based on existing forecasts and because it will take time for some new policies to see money pass to the beneficiaries. The Bank of England's latest interventions

will feed through to debt as soon as gilts are purchased or TFS loans drawn down.

Public sector net borrowing (PSNB) is provisionally estimated to have shown a deficit of £0.3 billion in February. This compares with a deficit of £0.6 billion last February. Year-to-date borrowing was up £4.2 billion (10.4 per cent) on the same period last year.

Central government receipts (excluding PSNB-neutral transfers related to ‘quantitative easing') were up 3.0 per cent in February and 2.8 per cent over the year to date. Central government

spending was up by 0.9 per cent in February and 2.7 per cent for the year to date.

Net debt was 1.1 per cent of GDP lower in February 2020 than a year earlier.

Comparisons in this commentary to our most recent forecast, published on 11 March, are unlikely to be particularly informative about the full-year picture. The pre-measures forecast was

closed in mid-February, when the impact of coronavirus on the UK looked likely to be limited, so it did not assume the sort of deterioration we might now expect in the final month of the year.

Full commentary

1. The Office for National Statistics and HM Treasury published their Statistical Bulletin on the February 2020 Public Sector Finances this morning, covering the first eleven months of 2019-20.1

Each month the OBR provides a brief analysis of the data and a comparison with our most recent forecast, currently from the March 2020 Economic and fiscal outlook (EFO).

2. As we outlined in that EFO, the Treasury as usual asked us to close our pre-measures forecasts for the economy and the public finances some way in advance of the Budget - on 18 and 25 February respectively - so that it had a stable base against which to finalise its policy decisions. At that point, the impact of the coronavirus on economic activity in the UK - via world GDP

growth and UK export markets - was expected to be modest.

3. With the crisis only having a significant impact on economic activity relatively recently - and policy measures only being announced in the last few days - it remains to be seen how big an

impact they will have in what is now the final month of this financial year (especially in the initial outturn estimates that we would expect to be revised as more information becomes available). The impact will be much more apparent as we move through 2020-21.

4. PSNB is an accrued measure of borrowing, which means that income and expenditure are recorded when the underlying economic activity takes place rather than when any cash

payments take place. As a result, the initial monthly estimate of PSNB is largely based on forecasts that the ONS revises over time as more data come in. On the receipts side, the time taken to firm up initial estimates depends on the lag between activities that give rise to tax liabilities occurring and the resulting cash payment to HMRC. For some taxes (such as fuel duty and stamp duties) this lag is very short as taxes are paid almost immediately. PAYE income tax and NICs are paid with a single month's lag and so March liabilities for these taxes will be largely known in April. VAT is generally paid one-to-three months after the economic activity

took place. For other taxes the lags can be longer - notably small firms' corporation tax.

5. The relationship between cash and accrued receipts in the data is typically proxied via a simple time-shifting methodology - for example, PAYE cash receipts in April are used to estimate

accrued receipts for March. The forecasts included in the initial monthly estimate for receipts would usually be based on a monthly pattern consistent with the most recent fiscal forecast or with trends that have emerged in the months after the forecast. In general, this would mean that the impact of coronavirus on the tax base may not be immediately apparent in the cash receipts data and less so in the accrued receipts data that feed into estimates of PSNB. Instead,

a full picture of the impact will emerge over a number of months.

6. This will be complicated further by the fact that some companies in sectors that have experienced dramatic falls in revenues will not make the cash payments associated with previous periods' liabilities – through agreed ‘time to pay' arrangements or perhaps unilaterally. The large-scale support being provided through the business rates regime will not affect real-world receipts until April when they take effect. It is not clear at this stage how such adjustments will be reflected in the early estimates of the public finances data.

7. There are also lags on the spending side. Estimates particularly at the start of the financial year are largely based on departmental forecasts. Over time these become more refined, but they are not final until after the year end when spending has been audited. For a large organisation like the NHS, where all efforts are focused on addressing the public health crisis, the extent to which expenditure rises faster than previously planned may not be clear for some time. Where the policy response is being provided via local government (for example, with respect to adult social care), the time it takes to be reflected in firm outturn data might be even longer.

8. Cash measures of the deficit should be affected more quickly than the headline accrued measure. Public sector net debt will also be affected immediately by shortfalls in receipts and increases in cash outlays – both expenditure and loans. It will also be affected as soon as the Bank of England's latest interventions are implemented. (With the Bank's gilt purchases starting today, initial effects will be seen in next month’s release). Gilt purchases will change PSND to the extent that the Bank pays more or less for them than the nominal value at which they are recorded in the public finances. If the accounting treatment of the new Term Funding Scheme is the same as the existing one, all loans issued will add to PSND (as they are not liquid assets, so do not net off, whereas the reserves that finance them do add to PSND).

9. We will use our monthly commentary in forthcoming months to provide as clear a picture as we can of how the coronavirus impact and policy response is feeding through to the data.

Public sector net borrowing

10. Public sector net borrowing (PSNB) recorded a £0.3 billion deficit in February, compared with a £0.6 billion deficit last year. This was £0.5 billion lower than market expectations. A £1.9 billion rise in central government (CG) receipts was only partly offset by a £0.6 billion rise in CG spending. Borrowing by local authorities was up by £0.8 billion, while borrowing by public corporations was up by £0.3 billion.

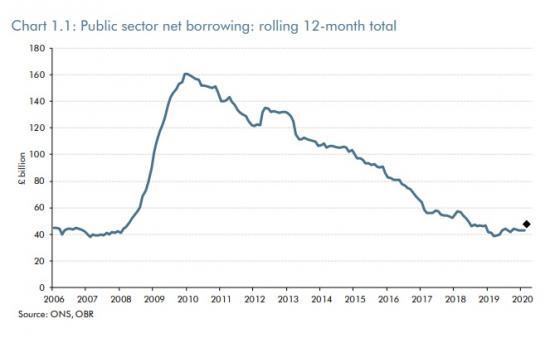

11. Borrowing over the first eleven months of 2019-20 is up £4.2 billion (10.4 per cent) on a year earlier. Borrowing over the first ten months of the year was revised down £1.1 billion in this release, more than explained by a £1.7 billion downward revision to local authority borrowing. Our March forecast assumes an £8.3 billion rise in borrowing over the full financial year. Chart 1.1 shows outturn PSNB on a 12-month rolling basis.

Central government spending

13. Relative to last year, total CG spending in February was up just 0.9 per cent. As in previous months of 2019-20, other current spending (mainly reflecting departmental spending) rose strongly – by £2.2 billion or 8.5 per cent. This was largely offset by a £1.5 billion fall in EU contributions, though this is just a timing effect following the large rise last month. For the year to date, CG spending is up 2.7 per cent on a year earlier, with other CG current spending up 7.6 per cent. Chart 1.3 shows CG spending growth on a 12-month rolling basis.

Debt

14. Public sector net debt (PSND) in February was down 1.1 per cent of GDP from a year earlier. This is in line with the 1.1 per cent of GDP drop in PSND assumed in our March forecast for the end of 2019-20. But to the extent that the Bank of England’s latest gilt purchases and TFS loans are implemented before the end of March, this forecast will be overtaken by events.

To see the graphs and other Data go HERE