Getting Over Covid Speech By Andrew Bailey, Governor Of The Bank Of England

8th March 2021

On Monday 8th March 2021 Andrew Bailey, Governor of the Bank of England talks about the post-Covid future as the economy recovers from the pandemic.

He examines the nature of the shock to the economy and looks at how it may change the way people work and shop. He says it's important to boost investment and productivity growth, to raise the sustainable rate of growth of the economy.

And he sets out what this means for the monetary policy action we take.

Speech given by Andrew Bailey, Governor of the Bank of England

Resolution Foundation - 8 March 2021.

Introduction

It's a great pleasure to be participating in a Resolution Foundation event today. I wish I could say what a pleasure it is to be at the Foundation, but that has to remain a hope for the future.

I am going to talk today about the future, the post Covid future as the economy recovers from this traumatic experience. If I had to summarise the diagnosis, it's positive but with large doses of cautionary realism.

To summarise, after starting with some description and assessment of the Covid shock to the economy, I am going to draw out four important points:

Covid has been both a demand and supply shock to the economy, and the recovery therefore has to be in both elements, unusually so for recoveries I think. Absent a dual recovery, dealing with the issues that arise will be more difficult.

Second, there are reasons to believe that so-called longer-term scarring damage to the economy will be more limited than in some past recessions, but there will most likely be structural change which will influence the future of supply and demand.

Third, it is important to boost supply capacity to raise the sustainable rate of growth in the economy and thereby ease the task of managing the necessarily higher level of public and corporate sector debt.

And fourth, taking all of this together, and consistent with the current setting of monetary policy and the outlook for the economy as set out in the February Monetary Policy Report, it is important to emphasise the role of the forward guidance that the MPC has adopted, and the announcements made a month ago on so-called toolbox issues.

The Covid Economy

The economic impact of Covid has in aggregate been very large. We expect that by the end of the first quarter, UK GDP will still be around 12% below its level at the end of 2019, a huge shortfall. The impact has been synchronised across economies - the similarities of this shock far exceed the differences in terms of economic impact. That said, within economies - the UK included - the impact of Covid has been highly uneven across sectors. Those that conduct activity involving large amounts of close human contact have obviously been most seriously affected. I would add that this has led to other notably uneven and unequal effects, because these sectors tend to have higher proportions of low paid workers, female workers, and there is a concentration by ethnicity as well. This is an issue the Resolution Foundation has done some commendable work on (Cominetti et al, 2021).

A common question that we ask about economic shocks is whether it is a demand or supply shock. As monetary policymakers we ask this question with good reason - the identification of shock type matters for the impact on spare capacity and inflation. So, what is the answer for Covid? The answer appears to us to be both: demand and supply. This is not surprising - shutting large parts of the economy down to protect against infection affects both demand and supply. But this is highly relevant to the task of getting over Covid, and for monetary policy.

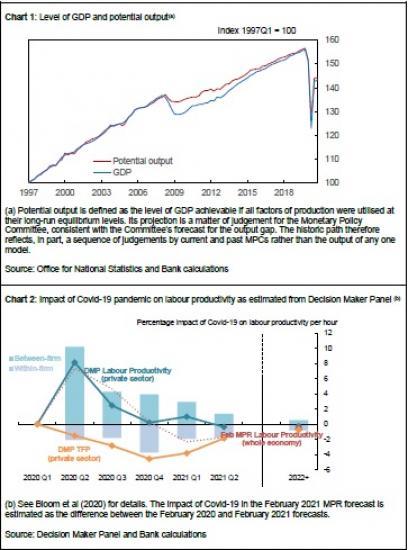

Let me try to illustrate the nature of the Covid shock through the lens of aggregate demand and supply. The first point to make is that illustrating the shock through a calculation of the output gap alone isn't very helpful, precisely because it is the net of two shocks. In Chart 1 I have therefore shown the historical path of aggregate demand (GDP) and supply (potential output) over the last twenty years, consistent with past MPC forecasts. I would caution against over-interpreting the detail of this chart, as there are several ways to represent aggregate supply and demand, and thus the output gap. But, detail notwithstanding, it is clear that while a gap has opened up between demand and supply during the Covid pandemic, the overwhelming feature is the coincident hit to both demand and supply. That stands in marked contrast to the more pronounced impact on demand following the global financial crisis, and persistent period of spare capacity thereafter.

As well as the Covid shock, the behaviour of supply and demand also reflects the nature of the policy response, and in particular the so-called furlough scheme (the Coronavirus Job Retention Scheme). By temporarily supporting jobs, this scheme has avoided a much larger spike in unemployment, which would other things equal have resulted in a smaller fall in supply and a much wider margin of spare capacity.

For a monetary policy maker interested in the output gap and how it will evolve in the recovery from Covid, it is clear we need to focus on the recovery of both supply and demand. More so than usual, the recovery from Covid requires a recovery of the supply side. Some of the effects on supply directly related to restrictions on activity and voluntary social distancing are likely to be temporary, and should start to reverse as the health outlook improves and along with the vaccination programmes enable restrictions to be eased. Changes in supply due to so-called scarring and structural change are though likely to be more persistent.

To what extent is the nature and form of economic activity likely to change?

I want next to take a look at a number of key aspects that will underpin the recovery, and in doing so address a further important question, namely to what extent is the nature and form of economic activity likely to change, and what will be the implications of that change?

In the November Monetary Policy Report (also Ramsden, 2020) we covered this ground under three headings: what we buy; what we make; and how we work. The key point is that the impact of Covid has required and encouraged very sizeable adjustments, but it is far from clear whether or to what degree these will persist post-Covid and therefore what will be the longer-term impact on the economy. Let me briefly describe and assess some of the major changes.

Last autumn, estimates suggested that around a third of workers in the UK undertook at least some of their job away from their normal place of work. As we all know, remote working has become much more common and businesses have delivered services in new ways, often using technology to reduce personal contact. Prior to Covid, only 5% of people in employment worked mainly from home.

There have also been notable changes in the way we consume. Online shopping has surged during the pandemic, accelerating a pre-existing trend. The latest retail sales figures indicate that it accounts for 35% of total sales, up from 20% in February last year. Online retailing has the potential to be more productive than through physical stores, and there is some evidence from the last decade of this already happening. Higher productivity growth in retailing has not been fully matched by higher wage growth, and this lower unit cost growth may have contributed to the relative weakness of domestic consumer prices in recent years (Tenreyro, 2020).

Covid has also caused changes in consumer spending patterns. Much of this has been of necessity, but if some changes to consumer spending habits persist - for instance if tastes change - the pattern of production in the economy is also likely to change. The question is how will such a process of more structural change in the economy happen, and what will be the impact?

What are the implications of the changes we are seeing in the economy?

This is a very big question, so what follows is necessarily quite high level. The answer to the question is surrounded by a great deal of uncertainty, given the scale and speed of the shock that has caused the changes.

Let me start with employment and the labour market. In normal UK economic cycles, falls in output are accompanied initially by relatively small falls in hours worked and then later by larger falls in employment. Employment, total hours worked and unemployment all tend to be highly persistent, so a rise in unemployment means - based on history - that it will be higher a year from now. That said, the UK labour market has adjusted relatively quickly to large shocks in the past (Broadbent, 2012). In normal times, around 9% of workers change jobs every year, but the tendency to persistence provides evidence from the past of the effects of a mismatch between the skills of job seekers and those required by hiring firms. As I noted earlier, some of the sectors hardest hit by the pandemic employ more young and low-skilled workers, who may find it hard to move between sectors (Haldane, 2020). That difficulty will be amplified if the jobs involve different tasks.

Bank staff have analysed the task content of different jobs to quantify the extent of task reallocation required in various scenarios. In a relatively extreme scenario where the pattern of consumer spending is unchanged from 2020 Q3, staff estimate that the extent of the task reallocation over coming years would be higher than in the recent past, but much less than occurred during the 1980s and early 1990s. That was a period of significant structural change during which the share of employees working in the manufacturing sector fell from 26% to 16%.

There are two important points I would emphasise here. First, the variation in skills demanded by employers across industries has probably shrunk in a more service oriented economy, which would assist transition where it is needed. And second, policy intervention, particularly the furlough scheme, will help to preserve viable employment going forwards, and skills specific to particular jobs or companies, which is a good thing. Ahead of its May Monetary Policy Report, the MPC will assess the impact of the extension of the furlough and related schemes, announced in last week's Budget.

My expectation would be that this is likely to reduce the peak level of unemployment over the coming months. However some rise in unemployment as the scheme tapers will be hard to avoid.

Just as workers are often specialised, capital such as plant and machinery can be specialised for specific tasks. The more specialised capital is, the harder it is to redeploy. Bank staff have estimated capital "redeployability" scores for different types of assets using a similar approach to Kim and Kung (2017). Information and communications technology, machinery and buildings tend to be highly redeployable, with uses across many industries. In contrast, there are few alternative uses for aircraft.

Capital may also be in the wrong location even if the pattern of output is similar, if Covid results in such a change of location, for instance related to the rise of home working. It is also reasonable to think that there is, and will be, considerable uncertainty over which changes in demand will prove temporary and which will persist (Vlieghe, 2020). We do know that as of now many people expect working from home to remain more common after the Covid pandemic is over. Half of new remote workers say they would like to continue to work from home all or most of the time even when lifting restrictions permits a return to normal working patterns (Felstead and Reuschke, 2020).

Employers in some sectors also expect the proportion of staff that regularly work from home to more than double (Chartered Institute of Personnel and Development, 2020 and DMP, 2021)1, and many contacts of the Bank's Agents expect a hybrid model of two to three days a week spent in the workplace to become the "new normal" for office workers.

What is the evidence so far for the impact of Covid on productivity and investment? Here we can turn to the information that comes from the regular surveys of the Bank's Decision Maker Panel (DMP) (Bloom et al., 2020). Labour productivity in the UK tends to be pro-cyclical. This does not appear to be the case in the Covid shock. So far during the pandemic labour productivity per hour appears to have risen, but with a tendency to reduce over time (Chart 2). There is, however, a lot more going on under the surface. There has been a negative impact on productivity resulting from measures taken to contain Covid. Firms in the DMP estimated that Covid has increased average unit costs by around 7% in the second and third quarters of last year. They expected this impact to reduce to 5% by the second quarter of this year, with a more persistent negative impact of 2%. All of this reflects new costs - for PPE, screens etc., and the impact on costs from social distancing reducing capacity.

However, this negative effect from higher unit costs was offset for DMP members by what is often called a batting average effect - namely that the impact of Covid has shifted the composition of activity towards higher productivity firms. But this means that Covid has seen lower total output and higher average labour productivity. This is consistent with the greater than normal supply side impact of the Covid shock. But this is not creative destruction in a Schumpeterian sense; in other words that raises output through competition and innovation. Rather, this is a form of destruction that lowers total output and welfare.

I should also note that evidence on the impact on productivity resulting from greater working from home is not clear (Barrero et al., 2020 and Haldane, 2020). Reduced travel time is a positive, but there may be lower innovation and creativity which would otherwise come from people being together more.

I want to finish this section on the economic implications of Covid by highlighting two longer-term and important developments, both of which pre-date Covid, and neither of which is helpful. First, the UK has experienced a fall in the average rate of growth, reflecting slower growth in potential supply capacity.

Chart 3 illustrates the four-quarter GDP growth rate since 2000. It is apparent that the average growth rate has fallen from around 2.5% in the years before the global financial crisis, to around 1.5% in the period immediately prior to the Covid pandemic. Chart 4 shows the same timeline for aggregate labour productivity per hour over the last twenty years. Again, the story is not encouraging. Another way of representing this, is to note that the level of activity in the UK following the global financial crisis is significantly below its level at the equivalent stage following the 1930s Depression (Haldane, 2021).

Issues arising in the recovery from Covid

I want to return now to the four important points I set out at the start.

First, Covid has been a shock to both demand and supply in the economy. Using an output gap measure on its own fails to capture the importance of this story. The best we can say is that how the output gap develops in the recovery from Covid will depend on the net effect of the two, both of which will need to move by more than in normal recoveries.

There is another element to this part of the story which is hard to assess at present, namely to what extent the more structural changes we have seen during the Covid crisis will persist, and what effect they will have on the recovery? There is a lot of uncertainty around these elements, but my best guess is that we will see some persistence, not full persistence but not a full reversion to pre-Covid either. We will work more from home than we used to and shop more on-line because new habits will persist to some degree, and to the extent they unwind it will be over a period of time.

The second point is that I see reasons to believe that the longer-term negative economic effects of the Covid shock will be smaller than we have seen in the past, particularly in the 1980s and early 1990s. As I described earlier, it seems likely that task and job reallocation and capital redeployment has increased since then, for instance because workers will need less significant retraining to move between sectors. In our assessment, the supply capacity of the economy is expected to be around 1¾% lower than it otherwise would have been in the absence of Covid by the end of our forecast period. But, of course, there are risks on both sides of this assessment.

The third point is that, although those sectors which are growing may require new capital, elevated uncertainty is expected to continue to reduce investment other things equal, weighing on the capital stock and productivity growth. I have just used the phrase "other things equal" to describe the likely path of investment. However other things ought not to be equal going forward in my view.

I mentioned earlier that we have had a decade or more of slower growth and weaker productivity growth. And, as Chart 5 shows, although business investment did recover from a low base following the global financial crisis, it too was weak in the period prior to the Covid pandemic. This was only partially offset by growth in government investment, which has also generally been weak over the same period (Chart 6). The effect of this weakness in investment can also be seen by looking at capital services - a measure of the value of the flow of services which are derived from the capital stock, including machinery, equipment, software, structures, and land improvements. This may better capture the drivers of supply growth than looking at growth in investment alone. It shows a sharp decline following the collapse in investment during the global financial crisis, and a subsequent recovery, which flattened off as a result of the weak investment in the period prior to Covid (Chart 7).

The Covid shock has been profound, and has required an increase in public and business debt to smooth the impact. This is a necessary and sensible response. It means that the economic impact of Covid will be spread over time - how long we don't know because it is too early to predict. But that cost has to be managed, and it will be easier to do that with a higher trend rate of growth, boosted by stronger investment. Let me add that this investment is also needed to support the transition required by climate change and the necessity of enabling a more digital economy. These are challenges and opportunities. The message is simple: stronger growth in potential supply supported by stronger investment and productivity growth will make the Covid recovery easier.

Monetary policy has a role to play here, in ensuring there is sufficient growth in demand to match any increase in potential supply growth. The MPC's actions during the pandemic may also have helped reduce the extent of scarring. The Bank's Financial Policy Committee is also taking steps to ensure there is appropriate supply of finance for productive investment. As part of this work, the Bank, alongside the Treasury and the Financial Conduct Authority, has convened an industry working group, to help overcome some of the barriers to investment in productive finance. And finally, growth in potential supply is also being supported by fiscal policy. Last week's Budget, and the Build Back Better policy paper released by the Government alongside it, outlined a range of measures the Government is taking to support economic growth through significant investment in infrastructure, skills and innovation.

Let me end on the fourth point, what does this all mean for monetary policy? There is a growing sense of economic optimism, in markets and in consumer and business confidence measures. The rate of new Covid infections is declining, and the vaccine programme is a huge achievement. There is light at the end of the tunnel. A note of realism though: our latest forecast in essence painted a picture of an economy that starts at a lower level of activity as a result of the current restrictions and people's natural caution associated with the renewed onset of Covid, which then gets back to where it was pre-Covid by the early part of next year. The level of activity in a year's time is broadly similar in the February forecast as it was in our November forecast, although the recovery is faster because the starting point is lower.

There is good news in that projection, with a rapid recovery later this year, and inflation returning to around our 2% target. That recovery is assisted by the continued support the MPC is providing through low interest rates and quantitative easing, and in my view it amply justifies our current stance on monetary policy. But let me dwell for a moment on three important elements of the MPC's decisions. First, we will continue to execute the announced programme of asset purchases, which we expect to be completed by around the end of 2021. Second, we have in place an important piece of forward guidance, which states that:

"If the outlook for inflation weakens the Committee stands ready to take whatever additional action is necessary to achieve its remit. The Committee does not intend to tighten monetary policy at least until there is clear evidence that significant progress is being made in eliminating spare capacity and achieving the 2% inflation target sustainably".

This guidance is a recognition of the scale of the shock, the high level of uncertainty and the risks around the Covid recovery, which are still on balance distributed on the downside, though less so as time goes by. It is deliberately state contingent, in other words it sets out that there is a burden of proof we will need on the sustainability of the recovery. But it does not deviate from the usual medium-term nominal anchor, the 2% inflation target. And in this context it is encouraging that measures of inflation expectations have remained relatively stable in the UK, despite the seismic shocks and unprecedented policy response we've experienced over the past year.

This recognition of the uncertainty and risks around the recovery has been backed up by separate decisions the MPC took in February on the toolbox measures we can employ. We have been quite clear these toolkit decisions should not be interpreted as a signal about the future path of monetary policy. We decided to ask the banks to make preparations within the next six months, in case we need to use negative interest rates to provide further support. This implies nothing about our intentions in that direction, and nor does it imply that negative rates are our chosen marginal policy tool, something that in my view is state contingent at all times.

We also signalled that the Bank will do work on the approach it would take to tightening policy, should that be needed, again recognising that it has more than one tool to do so.

These decisions are detached from our current or likely future policy decisions, but do recognise the increasingly two-sided nature of the risks we face, as we hope and expect to see the economy get over Covid.

Thank you

To read this article with all of the Charts mentioned go HERE