Ineffective Savings Accounts - Most Low Income People Do Not Benefit

6th April 2024

Today 6 April 2024 marks the beginning of a new ISA (Individual Savings Account) year with savers able to squirrel away up to £20,000 over the next year, with the returns being completely tax free. This is the Government's flagship policy to promote saving - with around 12 million adults benefiting in 2021-22.

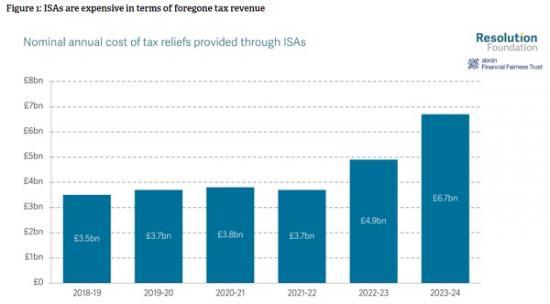

But while the policy is well intentioned - one-in-three working-age adults live in families with savings of less than the £1,000 - it is expensive and growing in cost. The tax relief offered through ISAs is expected to cost the Treasury £6.7 billion in 2023-24, up from £4.9 billion in 2022-23.

Furthermore, ISAs are poorly targeted. Vastly more tax-relief is given to those on higher incomes as they are more likely to have an ISA and more likely to have substantial ISA savings.

In 2018-20, 1-in-2 (54 per cent) working-age families in the top 10 per cent of the income distribution had an ISA, compared to less than 1-in-5 (18 per cent) in the bottom 10 per cent. Similarly, nearly half (48 per cent) of ISA holders with incomes over £150,000 had ISA savings exceeding £50,000, whereas the vast majority (65 per cent) of ISA holders with incomes less than £10,000 had savings of less than £5,000 in their ISA.

Finally, ISAs are also ineffective at raising long-term saving - for example, when the ISA allowance was increased between 2013-14 and 2014-15 this had no noticeable impact on aggregate household saving. Despite this, Government is doubling down on its existing approach to boosting savings by announcing that it intends to introduce a ‘UK ISA', with an extra £5,000 of tax-free savings going to those investing in UK-based assets.

This additional tax-free allowance will only benefit those that have more than £20,000 to save. In 2020-21, only 7 per cent of ISA holders (1.6 million people) maxed out their annual ISA allowance. Given the relatively small amount already saving £20,000 a year, the new UK ISA is unlikely to shift the dial on aggregate household saving.

Happy new ISA year, to all those who celebrate! For those lucky enough to be saving up to £20,000 this year, today is a significant date as it fires the starting gun on the opportunity to receive interest income and capital gains without having to pay tax. As ISAs are the primary way the Government is tackling UK families' chronic lack of savings - one-in-three working-age adults live in families with savings of less than £1,000 - it is important to ask whether this policy is working as it should. So in this Spotlight we put the new ISA year in context by setting out the key facts on their costs and benefits, along with how the Government's new ‘UK ISA' might change the picture.

ISAs are expensive

ISAs are hugely popular: there were over 22 million holders in 2020-21 - meaning that around 2-in-5 (42 per cent) UK adults had an ISA. ISAs work by offering a tax-free method of saving or investing money, with individuals exempt from paying tax on any income (i.e. dividends, interest and bonuses) or capital gains they receive from their ISA savings and investments. Millions take advantage of this tax relief every year: in 2021-22, £67 billion was deposited into 12 million adult ISAs.[1]

The cost to the exchequer from foregone tax revenue on ISAs is large. Figure 1 shows that the value of this tax relief has risen steadily risen over time. 2023-24 is expected to be an expensive year for Treasury, with HMRC projecting that the cost will rise to £6.7 billion, up from £4.9 billion in 2022-23. This increase in cost is largely the result of higher interest rates boosting returns on savings. However, policy decisions, such as decreasing the dividend allowance from £2,000 to £1,000 and capital gains tax-free allowance from £12,300 to £6,000, also boosted the amount deposited into ISAs and the cost of tax reliefs provided through ISAs.

Tax-free ISA savings will remain a costly tax-break for the Treasury for the foreseeable future. With interest rates anticipated to stay elevated - market pricing suggests Bank Rate will remain above 3 per cent until at least 2028-29 - returns on ISAs will continue to be high. Given the substantial and growing tax revenue forgone, there should be more scrutiny of the efficacy of ISAs in encouraging overall saving levels, particularly among the most vulnerable.

ISAs are a poorly targeted policy and overwhelmingly benefit the better off

ISAs tend to provide the most support (via tax relief) to those on the highest incomes, as this group are more likely to have ISAs and tend to have larger ISA savings pots. For instance, in 2018-20, 1-in-2 (54 per cent) working-age families in the top 10 per cent of the income distribution had an ISA, compared to less than 1-in-5 (18 per cent) in the bottom 10 per cent.

Despite the stated aim of ISAs being to encourage higher long-term savings particularly among people on low incomes, it's striking that this group has the lowest levels of ISA savings. Figure 3 shows that almost two thirds (65 per cent) of ISA holders with incomes less than £10,000 had less than £5,000 saved in their ISA. In contrast, nearly half (48 per cent) of ISA holders with incomes over £150,000 had ISA savings of £50,000 or more - considerably higher than all other income groups. In fact, in 2018-20, the richest tenth of working-age families owned close to a third (29 per cent) of all ISA savings.

Another reason ISAs are poorly targeted is the generous annual allowance, which at £20,000 currently it is equivalent to two thirds (67 per cent) of typical earnings (£29,700), and above what most people, especially those on low incomes, are able to save in a year. The latest data show that only 7 per cent of all ISA holders (1.6 million people) maxed out their ISA(s) in 2020-21. Unsurprisingly, ISA holders with the highest incomes were more likely utilise the full £20,000 allowance: 38 per cent of ISA holders with incomes above £150,000 maxed out their ISA allowance in 2020-21, compared to just 6 per cent among ISA holders with incomes of £20,000-£29,000.

Figure 5 shows that, in 2018-20, families with an ISA in the middle of the income distribution saved an average of £160 a month, totalling £1,920 annually - around £18,000 less than the annual ISA allowance. In fact, only around 1 per cent of families with an ISA had average monthly savings sufficient to exceed the £20,000 annual ISA allowance. As a result, current high level of the ISA allowance primarily benefits the very wealthy. Given these reported monthly saving rates, it is difficult to justify such a generous annual allowance, let alone advocate for further increases.

The evidence suggests ISAs are ineffective at incentivising higher saving

There is also little evidence to suggest that ISAs have encouraged greater saving. For instance, when the annual ISA savings allowance was raised significantly in 2014-15 (from £11,520 to £15,000) there was a significant inflow into ISAs, with the total amount deposited increasing from £57 billion to £83 billion between 2013-14 and 2014-15. However, as Figure 4 shows, this had no perceptible impact on the household saving rates, with the adjusted saving ratio (which measures the percentage of gross disposable income that households have left after consumption) actually falling from 2.4 per cent to 1.6 per cent over the same period. This is consistent with the idea that much of the flow into ISAs would have otherwise gone into other savings products and so been subject to tax. This is also supported by wider evidence that tax reliefs do little to incentivise greater saving. It's often the case that people who already have savings move their money around to maximise returns.

Despite the evidence that ISAs have not been effective, the Government is doubling down on this approach

The Government appears to be doubling down on these tax breaks by announcing the introduction of the ‘UK ISA' at the Spring Budget. This new product would have its own £5,000 annual allowance in addition to the existing £20,000 annual ISA allowance. The rationale behind this is to provide individual investors with an additional opportunity to save while also addressing the UK's low business investment performance. In practice, the new UK ISA and additional £5000 allowance only matters for those that have more than £20,000 a year to save. Given that very few people do max out their ISA allowance, the new UK ISA is unlikely to attract substantial amounts of additional investment, meaning that it won't shift the dial on aggregate saving.

From today, ISAs have been available for 25 years, but they have done little to address the problem of low savings in Britain, with as many as 1-in-3 (30 per cent) of working-age adults living in families with savings below £1,000. For this reason, we have previously made the case that ISAs should at least be capped at £100,000. The tax revenue raised from such a policy could be spent on expanding Help to Save - a saving policy specifically targeted at low income families. More recently we have shown that ‘behavioural' interventions are much more effective at boosting saving, with the most obvious example being pensions auto-enrolment. This suggests that getting serious about addressing the UK's low savings problem means shifting the policy emphasis away from financial incentives and putting behavioural framing at the heart of the strategy. With this in mind, we have previously outlined how a more cohesive and flexible savings policy framework could increase saving for precautionary and retirement purposes.

This will involve expanding pensions auto-enrolment while allowing for some degree of flexibility around pension savings to help meet precautionary needs during working life. Getting serious about boosting the chronic lack of UK household saving means being creative about how we design saving incentives rather than bolting new gimmicks onto the ISA system.

Read the full article with graphs at the Resolution foundation HERE

Richard Murphy writes about the need for reforms including ISA's in his The Taxing Wealth Report 2024

Precautionary tales

Tackling the problem of low saving among UK households

Families in Britain are confronted with what can be termed a ‘triple savings challenge'. This encompasses a lack of accessible ‘rainy day' savings to cushion small cashflow shocks, inadequate precautionary saving to see people through large and unexpected income shocks, and insufficient saving to provide an adequate income in retirement. These three savings challenges are intrinsically linked. However, existing policies have treated them as separate objectives creating a tension where families must choose between saving for precautionary purposes, or saving for retirement.

This report draws on behavioural insights and lessons from how other countries navigate the same issues to outline how the UK's savings policy architecture can be transformed to provide a joined-up solution to Britain's triple savings challenge.

Key findings

As many as 1-in-3 (30 per cent) of working-age adults live in families with savings below £1,000, leaving them financially vulnerable and ill-equipped to respond to small cashflow shocks.

Larger precautionary savings balances would help people cope with bigger shocks, but the country's savings shortfall is significant. If every working-age family in Britain had at least three months' income in precautionary savings, aggregate savings would be £74 billion higher.

Saving for retirement is also too low. 39 per cent of individuals aged 22 to the State Pension age (equivalent to 13 million people) were undersaving for retirement when measured against target replacement rates of at least two third of pre-retirement income.

Policies to boost precautionary saving have largely involve fiscal incentives, such as tax breaks or bonuses based on account balances. These policies are expensive, exceeding £8 billion in 2023-24, and are inefficient as they disproportionately benefit wealthier households.

Pension auto-enrolment has transformed pension saving. Since the introduction of auto-enrolment, the proportion of employees with a pension climbed from 47 per cent in 2012 to 79 per cent in 2021 - an extraordinary policy achievement.

Precautionary and pension saving are in tension. Evidence indicates that when default auto-enrolment contribution rates were increased from 2 per cent to 8 per cent between 2018 and 2019, for every £1 reduction in take-home pay due to higher pension contributions, employees reduced their consumption by 34p, with the rest of the contribution funded through either lower liquid saving or higher debt.

Other countries alleviate the tension between precautionary and pension saving by allowing early access to pension savings under a variety of conditions so that they can also act as a precautionary savings vehicle. This offers insights into how the UK’s savings policy could evolve to help boost retirement saving while also making British families more financially resilient in the short term.