It's Time To Debunk The Belief That Tech Natives Are More Valuable

1st November 2024

The generational tech divide is narrowing. Daniel Jolles and Grace Lordan surveyed more than 1,400 UK and US professionals and write that the ability to manage your attention and minimise task-switching is more important than how old you were when you first used a keyboard. This makes intergenerational diversity and inclusion key for productivity.

Younger generations are often thought of as being technologically fluent in the latest tools, attracting the label of ‘tech or digital natives'. In times of great technological progress, this perceived familiarity with the latest technologies can eclipse the value of experience, devaluing older generations of workers and putting them at risk of premature unemployment. However, in recent years new technologies have become increasingly widespread and user-centric, and the technology usage gaps between generations has been closing.

Are "tech natives" more technically valuable?

The generational tech divide is narrowing. Daniel Jolles and Grace Lordan surveyed more than 1,400 UK and US professionals and write that the ability to manage your attention and minimise task-switching is more important than how old you were when you first used a keyboard. This makes intergenerational diversity and inclusion key for productivity.

Younger generations are often thought of as being technologically fluent in the latest tools, attracting the label of ‘tech or digital natives'. In times of great technological progress, this perceived familiarity with the latest technologies can eclipse the value of experience, devaluing older generations of workers and putting them at risk of premature unemployment. However, in recent years new technologies have become increasingly widespread and user-centric, and the technology usage gaps between generations has been closing.

Are "tech natives" more technically valuable?

As the newest generation to join the workforce, Gen Z (born between 1997 and 2004) is often labelled as "tech native". However, the primary technologies Gen Z are met with upon entering the workforce are often familiar ones, a modern version of the same Microsoft Office suite and email client that Gen X encountered when they first entered the workforce over 30 years ago.

It is assumed that growing up with the most recent technologies gives us the ability to use them better and capitalise on their benefits. Yet, while cloud-based software such as instant messaging, video conferencing, project management, file sharing and collaboration tools have all become more prevalent at work in recent years, their impact on job performance depends less on "tech nativism", and more on how effectively the tools are engaged with. Younger generations often report lower productivity at work. Given the pressures and distractions many cloud-based tools create, the ability to manage our attention and minimise task-switching appears more important to realising the productivity benefits of the technology than age or past experiences with the technology itself.

Growing up with the most recent technologies might not give "tech natives" a productivity advantage, but leaders might ask if increasing the proportion of younger "tech natives" boosts the adoption of new technologies in the organisation. Older generations of workers are commonly assumed to be less capable and more resistant to new technologies, a stereotype that is both widespread and socially accepted. The majority of recruiters have doubts over the technical skills of older candidates, and are twice as likely to select similarly experienced younger candidates than older candidates for tech roles.

Over the past 30 years, the dominant theory suggests there are two factors that determine individual adoption of new technologies. The first is how easy the technology is to use, and the second is how useful the technology is believed to be. As the most recent generation to enter the workforce has been "born and bred" on the latest technologies, does it make them more likely to adopt the new ones as they arise?

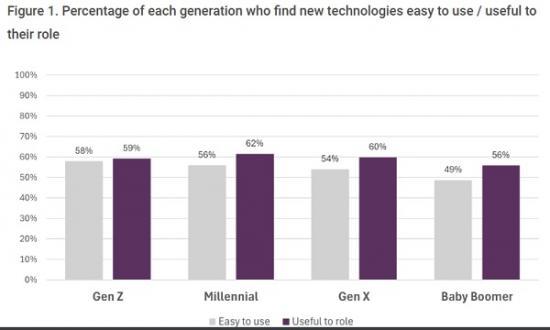

Surveying more than 1,400 professionals across the UK and US, we sought to explore generational differences in the perceived ease of use and usefulness of work-based technologies. A little over half of professionals find new work technologies easy to use (54 per cent) and consider them useful for their role (60 per cent). We also looked at generational categories, broadly understood as Gen Z, born between 1997 and 2004, Millennials, born 1981-1996, Generation X, born 1965-1980, and Baby Boomers, born 1952-1964. We found very limited differences between generations in attitudes towards technology (figure 1). Although professionals from younger generations were slightly more likely than older generations to say that they find new technologies easy to use and useful to their roles, these differences were insignificant. This suggests that there is no meaningful "gap" between the "tech natives" and more seasoned professionals in their attitudes towards new technologies at work.

Work context matters more than age

One of the limitations in making assumptions about technical ability based on generation is that it ignores the work contexts in which they operate. Workplaces that are intergenerationally diverse and inclusive are going to have different experiences with technology engagement and adoption of new tech initiatives than those that are not.

Only 60 per cent of employees view their firm as having intergenerationally inclusive work practices. These practices are important because they make it easy for different generations to gain support, fit in, develop regardless of their generation. Based on the data from 1,400 professionals across the UK and US, we found that 79 per cent of workers in firms with intergenerationally inclusive work practices are interested in and adopting the latest technologies in their work, compared to just 67 per cent in those without inclusive practices. Once again, there was no meaningful difference between the generations in their attitudes towards new technologies or their adoption of them in their work (figure 2).

These results are consistent with past findings that show that older generations of workers can be equally, if not more, positive than younger generations about the implementation of new technology initiatives. However, this is often dependent on the work context and the generational diversity in the workplace. Our results showed that younger generations in workplaces without intergenerationally inclusive work practices were less interested in using and adopting new technologies.

However, in workplaces with high levels of intergenerationally inclusive work practices, younger generations showed greater interest and adoption. In other words, maximising the engagement and interest of “tech natives” (younger generations) to adopt and apply the latest technologies at work, might require generationally diverse and inclusive environments.

Ditching tech nativism for tech inclusion

The perception that workers should be “tech natives” from younger generations to innovate and drive technology forward in the workplace has little evidence in practice. Initial findings from our research suggests that the intergenerational diversity and inclusion present in a firm provide important context for each generation's tech attitudes and behaviours. Additionally, individual differences in personality, gender, technology and work preferences can all influence attitudes towards technology. Regardless of generation, those who have chosen to pursue and persist with careers in technology are likely to be more technically proficient and enthusiastic than those who have not.

It is unclear how progress in generative AI will influence the generational tech divide. Some argue that these developments put older generations at greater levels of risk of redundancy, with AI acting as a substitute for accumulated experience by detecting patterns, making judgments of having their existing skills outdated. In other words, if AI is capturing historic information and data in a structured and succinct way, it can effectively manage the knowledge that would have been held by experienced and tenured employees.

However, others argue that generative AI reduces the reliance on technical skill, allowing older generations the opportunity to use their expertise and experience to craft prompts, bring context to AI outputs, and manage the complex workplace relationships needed for productivity. Despite the uncertainty, hiring preferences for “tech natives” based on AI-related role requirements are already emerging.

Relying too heavily on younger generations of “tech natives” to drive forward tech progress in any firm feels like a flawed strategy. There is little evidence that “tech native” employees hold more positive attitudes towards the technology than professionals from older generations or that their native tech experiences will help them to use technologies more productively at work. Rather, younger generations of “tech natives” appear most valuable to a firm when they are accompanied by a broader work context of intergenerational diversity and inclusion.

Authors

Daniel Jolles

Grace Lordan

Note

This article is from The London School of Economics. To read it with more links and graphs go HERE