The largest decline in annual GDP for 300 years

15th July 2020

The Office for Budget Responsibility(OBR) latest report.

The Fiscal sustainability report (FSR) usually focuses on long-term projections for the public finances and sustainability of debt. Typically, our most recent medium term forecast serves as the ‘jumping-off point' but as the March 2020 forecast was finalised in February before the full impact of the Coronavirus pandemic became clear, for this report we produced three scenarios for the medium term before extending our assessment to the long term.

The structure the report is as follows:

Chapter 1: describes the main conditioning assumptions underpinning our analysis and outlines our approach at each step of the process.

Chapters 2 (economy) and 3 (fiscal) lay out three medium-term scenarios that then serve as different starting points for our long-term sustainability analysis.

Chapter 4: the conclusions of the long-term sustainability analysis.

Chapter 5: devoting more space than usual to the risks to sustainability posed by the shock.

Executive summary

Overview

1 The coronavirus outbreak and the public health measures taken to contain it have delivered one of the largest ever shocks to the UK economy and public finances. Assessing fiscal sustainability in this context is challenging - it is difficult to predict what might happen from one month to the next, so projecting the fiscal position decades into the future might seem futile. But the pandemic has not displaced the long-term pressures that we typically focus on

in our Fiscal sustainability reports (FSRs), although it has significantly changed the baseline against which their impact will be felt. To capture those changes, this FSR presents three potential scenarios (‘upside', ‘central' and ‘downside') for the economy and the public finances over the medium term, assesses their implications for fiscal sustainability, and discusses how the pandemic and policy response has altered our assessment of fiscal risks.

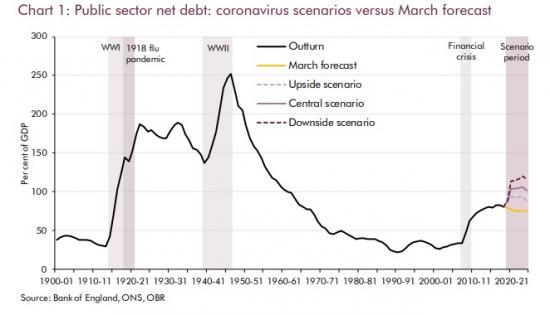

2 The UK is on track to record the largest decline in annual GDP for 300 years, with output falling by more than 10 per cent in 2020 in all three scenarios (and contracting by a quarter between February and April). This delivers an unprecedented peacetime rise in borrowing

this year to between 13 and 21 per cent of GDP, lifting debt above 100 per cent of GDP in all but the upside scenario. As the economy recovers, the budget deficit falls back. But public debt remains elevated, continuing to rise in the central and downside scenarios.

3 That said, the outlook would have been much worse without the measures the Government has taken. These have provided additional financial support to individuals and businesses

through the lockdown. They should also help to limit any long-term economic ‘scarring', by keeping workers attached to firms and helping otherwise viable firms stay in business.

4 Our upside scenario assumes that long-term scarring is avoided, but in the central and downside scenarios it reduces output in the medium term by 3 and 6 per cent respectively. By 2024-25 the budget deficit falls back to close to our March forecast of 2.2 per cent of GDP in the upside scenario, but it remains higher - at 4.6 and 6.8 per cent - in our central and downside scenarios. This would represent structural fiscal damage of 2.4 and 4.7 per

cent of GDP relative to our March forecast. None of the scenarios assume persistently lower growth in potential GDP, as was the case after the financial crisis and which would result in the loss of output and fiscal damage increasing over time. And they all assume that very low interest rates persist in line with market pricing, cushioning the fiscal blow. This helps stabilise public debt as a share of GDP after it has risen to a six-decade high.

5 The pandemic has hit the public finances at the end of two years during which fiscal policy has already been eased materially. This started in June 2018, when Prime Minister Theresa May announced a large NHS spending settlement, and was accelerated in Chancellor Rishi Sunak's Spring Budget this year. In it, he set out plans to borrow significant sums on an ongoing basis and merely to stabilise, rather than reduce, the debt-to-GDP ratio.

6 A key risk to this pre-virus fiscal strategy was that the highly favourable financing conditions the Government currently enjoys might not persist. In that event, the longer-term pressures

from health costs and demography we routinely highlight would need to be faced against the background of greater upward pressure on the ratio of debt to GDP. In the short term,

the pandemic has seen borrowing costs fall even further, which all else equal increases the scope for running a fiscal deficit while keeping debt stable as a share of GDP. But higher public debt also increases the sensitivity of the public finances to higher interest rates, increasing the risks from pursuing a fiscal strategy that assumes that financing conditions will remain favourable over the longer term. And having experienced a public health crisis

on this scale, there are also likely to be pressures to devote a higher share of GDP to spending on the NHS and wider care services in the future, including on adult social care.

7 In the short term, the Government understandably remains focused on controlling the virus and reviving the economy. Indeed, on 8 July, the Chancellor announced a further package of measures that the Treasury said would cost "up to £30 billion" this year, in addition to which a further £32.9 billion of departmental spending was also disclosed. But at some point, given the structural fiscal damage implied by our central and downside scenarios, the

longer-term pressures on spending, and the range of fiscal risks we identify, it seems likely that there will be a need to raise tax revenues and/or reduce spending (as a share of national income) to put the public finances on a sustainable path.

8 The Chancellor's latest measures were finalised and notified to us too late to be incorporated in our scenarios. They would have had a material effect had we been able to do so, but this would primarily affect the level of borrowing this year and the peak for public

sector net debt, rather than the level of structural borrowing in the medium term.

9 The Government's ability to push the deficit ever higher rests in part on the credibility of the institutional framework that gives investors confidence that the value of the government bonds they purchase will not be deliberately eroded in the future. Its willingness to push the deficit higher points to an increased reliance on the use of fiscal policy in ‘bad' times, which implies that debt will also need to fall more quickly in ‘good' times to build up fiscal space.

But the case for precautionary investment in fiscal space in good times runs directly against the encouragement to run larger deficits created by the favourable financing conditions.

These conflicting pressures will no doubt figure in the Chancellor’s deliberations as he designs the UK’s sixth set of fiscal rules in 10 years to guide his Autumn Budget and beyond.

Read the full report HERE 160 pages