A Pre-election Statement Putting The Autumn Statement 2023 In Context

25th November 2023

The Chancellor unveiled a much bigger-than-expected tax-cutting package in his Autumn Statement 2023, along with promises of more to come. Having been handed a forecast from the Office for Budget Responsibility that showed a cumulative improvement in borrowing of nearly £90 billion.

The Government has chosen to spend almost all of it, mainly on permanent tax giveaways. But this is a gamble. Not only will this leave the Chancellor with very low levels of headroom against future shocks, it rests on the back of implausible spending plans post-election.

In this briefing note, we put the decisions in the Autumn Statement 2023 in context, discussing how the economic outlook has changed, what that means for the public finances, and how the policy affects Scotland.

Around 40 per cent of the gains from the tax and benefit measures announced in the Autumn Statement - including cuts to National Insurance, boosts to Local Housing Allowance and changes to the Work Capability Assessment - go to the richest fifth of the population. The top 20 per cent gain £1,000 on average, five times the gains seen by the bottom fifth (£200).

Taken together, all tax and benefit measures announced in this Parliament remain progressive, with the richest fifth of households set to lose £1,100 on average, while the poorest 20 per cent gain an average of £700.

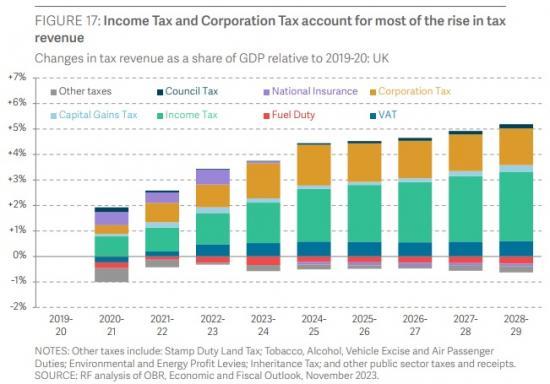

Taxes are up, not down. The Autumn Statement's £20 billion of tax cuts compare to around £90 billion of tax rises (including higher Corporation Tax) already announced this Parliament. Despite the tax-cutting rhetoric, taxes are rising by 4.5 per cent of GDP between 2019-20 and 2028-29, equivalent to £4,300 per household.

By not fully accounting for higher inflation in public services spending plans, unprotected departments such as Justice, Communities and Local Government and the Home Office are set to see their per capita day-to-day budgets fall by 14 per cent - equivalent to a real-terms cut of £17 billion - between 2022-23 and 2027-28.

Although nominal wages are growing faster than previously forecast, this simply reflects the reality of higher inflation. Real wage growth remains muted, and real average earnings are not forecast to return to their 2008 peak until 2028 - a totally unprecedented 20-year pay stagnation.

With just a year to go until the next General Election, this Parliament is on track to be the first in which real household disposable incomes have fallen (by 3.1 per cent from December 2019 to January 2025). Households will, on average, be £1,900 poorer at the end of this Parliament than at its start.

Read the full report HERE

Pdf 42 Pages