If the Chancellor wants to cut taxes, he should tell us where the spending cuts will fall

27th February 2024

Chancellor Jeremy Hunt will announce his second Budget, and fourth fiscal event, on Wednesday 6 March. This will possibly be the final fiscal event of the current parliament.

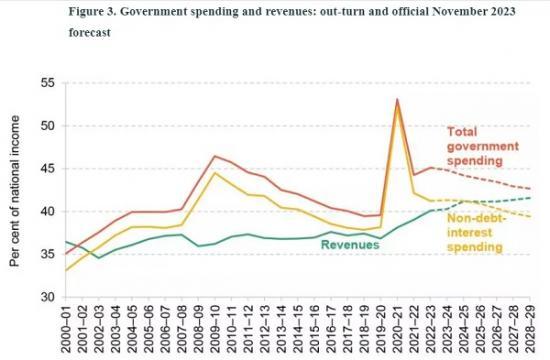

UK taxes are heading to record-high levels as a share of national income. The Chancellor is under pressure to announce cuts. But government debt is high and rising, and barely on course to be falling in five years' time - that being the fiscal rule the government has set itself. Unless the Chancellor is willing to spell out where the cuts will fall, the temptation to scale back provisional spending plans further to ‘pay for' new tax cuts should be avoided.

A report by the Institute for Fiscal Studies sets out how the fiscal outlook has changed since November.

Key findings

1. Borrowing in 2023-24 is now on course to be £113 billion, which would be £11 billion below the £124 billion forecast by the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) in the November 2023 Autumn Statement. Lower-than-expected inflation since November has fed through into lower spending on the portion of government debt linked to the RPI, while tax revenues have so far come in lower than initially forecast. But if data for the remaining two months of the financial year follow the same pattern seen so far, at 4.1% of national income borrowing this year would still be more than twice the 2.0% of national income borrowed before the COVID-19 pandemic. A reduction in forecast borrowing would doubtless be welcomed by the Chancellor, but we should remember that as recently as March 2022 the OBR was forecasting borrowing in 2023-24 would, at £50 billion, be less than half what we now project.

2. To finance our elevated borrowing in the next few years, we are now asking the private sector to absorb historically high volumes of debt. High gilt issuance, exacerbated by the Bank of England's quantitative tightening, is forecast to result in the biggest increase in private sector holdings on record of 7.9% of national income in 2024-25. Looking more broadly at the next five years, this is forecast to average 6.2% a year which is more than twice the 2.8% a year seen over the last 25 years.

3. We expect the OBR to reduce its medium-term debt interest spending forecast (for 2028-29) by £10 billion from £122 billion to £112 billion. The OBR takes market expectations for interest rates. These have fallen since it produced its November forecast, to below where they were a year ago, but they remain volatile. Even with this sizeable downward revision, spending on debt interest is forecast to persist around 2% of national income (or £55 billion in today's terms) a year higher than what was forecast prior to the pandemic.

4. The medium-term outlook for revenues will hinge on the forecast for nominal growth in the economy. We do not expect a big revision to the outlook for real growth in the economy, but the forecast for economy-wide inflation could be revised. All else equal, it would only take a downwards revision in the cash size of the economy of less than 1% to eliminate all of the £10 billion improvement in borrowing coming from lower forecast spending on debt interest.

5. New long-term population projections driven mostly by higher expected net migration help increase the size of the economy but will make existing spending plans even more challenging in per-capita terms. Under the OBR's November forecast, real-terms day-to-day spending on public services was set to grow by 0.9% a year on average from 2025-26 onwards. At the time, this translated into growth in per-capita spending of 0.5% a year. However, if we take the latest ONS population projections, the average annual growth in real-terms spending per capita falls to just 0.2% a year.

6. Whatever happens to the OBR's estimates of the government's ‘fiscal headroom', the economic case for tax cuts before the next Spending Review is completed is weak. The public finances remain in a poor position: at the Autumn Statement, the Chancellor was only just on course to meet his commitment for debt to be falling as a share of national income in five years' time. Despite this, debt was forecast to be persistently stuck above 90% of national income over the medium term. This is in sharp contrast to the not-so-distant March 2022 Budget, when official forecasts were for public sector debt in 2026-27 to be more than 13% of national income lower, and on a decisively downward path. Even if the outlook for borrowing did improve significantly, net tax cuts should not be implemented before the cuts implied by the current spending totals are allocated to individual departments.

7. Any new tax cuts announced in the Budget would only offset part of the record-breaking increase in tax revenues as a share of national income over this parliament. Even after the cuts to National Insurance in the Autumn Statement, official forecasts suggest that taxes in 2023-24 will be £66 billion higher than they would have been had their share of national income been held at its 2018-19 level. Tax revenue as a share of national income is forecast to continue rising so that in 2028–29 it will be equivalent to £104 billion bigger, in today’s terms, than it was in 2018–19. This increase is fuelled by freezes to thresholds in the personal direct tax system and the big increase in the main rate of corporation tax that was implemented in April 2023.

8. Continued freezes to rates of fuel duties would depress revenues. The Autumn Statement forecast assumed that the 5p cut to rates of fuel duties would be allowed to expire and that they would then increase each year in line with the RPI. Past behaviour suggests it is much more likely they will remain frozen at their current level in cash terms, which would reduce revenues in 2028–29 by £6 billion. Similarly, if business rate relief for retail, hospitality and leisure sectors – first introduced at 50% as a temporary measure during the pandemic and then increased to 75% and twice extended – continues then the cost of this tax cut, which was put at £2.4 billion in 2024–25, will persist.

9. The Autumn Statement forecasts were predicated on a fresh round of spending cuts. Public sector investment is planned to be frozen in cash terms, whereas maintaining investment (net of depreciation) at its current share of national income in 2028–29 would require an additional £20 billion of spending. While day-to-day spending on public services would rise in real terms by £17 billion overall, after accounting for plausible settlements for spending on the NHS, childcare, defence, schools and overseas aid, other areas of government would face real-terms cuts of £18 billion by 2028–29. This is equal to an average cut of 3.4% a year for four years or an average cut to per-person spending of 4.0% a year. It is possible that these spending plans will be delivered. But there is clear risk that whoever is in office after the next election is unwilling or unable to deliver them. Maintaining real-terms spending on unprotected services would require a cash top-up of £20 billion; maintaining it in per-capita terms would require a cash top-up of £25 billion.

10. Another risk to the credibility of the public finance forecasts is that a second fiscal event in 2024 occurs in the run-up to the general election if it looks as if the OBR’s fiscal forecasts will strengthen, but not if they appear likely to deteriorate. So far, Jeremy Hunt has tended to follow the pattern of Chancellors since 2010 in offsetting improvements but not deteriorations in the borrowing forecast, leading to a ratcheting effect over time. This pattern of fiscal choices means that the OBR’s ‘central’ forecast cannot really be thought of as central. It is exacerbated by frequent fiscal events that implement permanent policy changes in response to changes in ‘headroom’ that are small relative to the uncertainty inherent to any medium-term forecast.

11. Further tightening spending plans may appear to generate further ‘headroom’, but this would not be a transparent or credible strategy and the Chancellor should avoid this temptation. Specific and immediate tax cuts should not be ‘paid for’ by unspecified future spending cuts. Moving from 0.9% annual real increases in day-to-day spending to 0.75% (as the Chancellor is reportedly considering) would reduce planned spending in 2028–29 by £3 billion, but only by increasing the implied cuts to unprotected budgets by the same amount. Similar to this, the next fiscal event after the March Budget will see the forecasts extended to 2029–30. While this might – driven by tight spending plans being extended by a further year – be expected to reduce borrowing at the end of the forecast horizon by around £10 billion, the economic case for using this to finance tax cuts in advance of a detailed Spending Review would remain weak.

12. Tax cuts without tax reform would represent another missed opportunity. If the Chancellor is determined to cut taxes and wants to boost growth then better options exist than just cutting the rates of income tax, National Insurance contributions or inheritance tax. Stamp duties on purchases of properties and shares are particularly damaging taxes and should be towards the front of the queue for growth-friendly tax cuts. And tax reform that made our existing taxes less economically damaging could be easier to do in the context of a sizeable tax cut as it would help limit the extent to which some would lose out.

Read the full IFS report HERE