A U-shaped Legacy - Taking Stock Of Trends In Economic Inactivity In 2024

25th March 2024

In an election year, jobs and benefits are often centre stage. Alongside the UK's stagnant wage growth, there is one big issue that will face the next government: the rises in economic inactivity and health-related benefit claims.

Real pay growth, unemployment and vacancies have all returned roughly to 2019 rates. But there is one aspect of the labour market that remains far from normal: the UK employment rate is still lower than pre-pandemic, with economic inactivity up from 20.5 per cent to 21.8 per cent, equivalent to 700,000 people. And the continued rise shows little sign of slowing as the pandemic recedes.

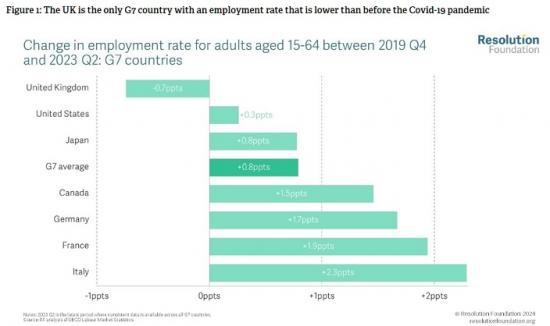

The UK is the only G7 country with a lower employment rate than before the pandemic.

This rise in economic inactivity has been U-shaped by age: those aged 16-24 and 50-64 account for nine-tenths of the rise in economic inactivity among working-age adults since the end of 2019.

And while there are more young people who are economically inactive and in full-time education (up 160,000, or 15 per cent, in the past year), it is the rise in economic inactivity due to long-term sickness that stands out. The number of working-age adults who are economically inactive due to long-term sickness has been growing for over four years and stood at 2.7 million in November-January 2024, having peaked at a record-high 2.8 million a couple of months earlier.

These developments are concerning, first and foremost for the 2.7 million people whose health and living standards are affected. But it is also a worry for the Treasury, with claims for illness- and disability-related benefits rising fast.

By December 2023, almost a third of people in receipt of Universal Credit (UC) had a health condition or disability that affected their ability to work, and again the pattern is U-shaped by age. More than half of claimants in their late fifties and sixties have a health condition or disability reflected in their UC award.

But UC claimants in their early twenties are more likely than those in their thirties or early forties to have a health condition or disability that restricts their ability to work, and it is among young adults that health-related UC awards have increased most significantly in recent years.

But it is the rising number of claims for PIP - the main non-means-tested benefit for those with health conditions or disabilities - that is most striking. Among working-age adults in England and Wales, new claims for PIP have increased by two-thirds (68 per cent) between early 2020 and early 2024.

Once again, it is those at each end of the age distribution who stand out. Older adults aged 55-64 are the age group most likely to claim PIP, but among young people, the rise in PIP claims in recent years has been most pronounced.

The number of new PIP claims in England and Wales is up 138 per cent for 16-17-year-olds, and up 77 per cent for 18-24-year-olds.

High economic inactivity remains the labour markey legacy of the Covid-19 pandemic

In many aspects, the UK labour market looks a lot like it did before the Covid-19 pandemic. After a rollercoaster four years, real pay growth reached 1.8 per cent in the most recent data for January 2024 - this is only slightly above real pay growth in 2019, which averaged 1.7 per cent. There is a similar trend when we look at vacancies: after peaking at 4.0 per cent, the vacancy rate has fallen back to 2.7 per cent, only slightly higher than the 2019 average of 2.5 per cent. And unemployment remains low, at just 3.9 per cent - this is the same as the average rate in 2019.

But one aspect of the labour market looks far from normal. The working-age employment rate in the UK is still well below where it was before the Covid-19 pandemic, down from 76.2 per cent to 75.0 per cent. Not only does this reverse the trend experienced in the UK in the 2010s (when the employment rate was rising consistently), it also sets the UK apart from its neighbours. As Figure 1 shows, the UK is the only G7 nation where the employment rate has not reached its pre-pandemic level. In fact, most G7 countries have seen their employment rate surpass its pre-pandemic level: on average across the G7, the working-age employment rate is up by 0.8 percentage points. As a result, the UK has fallen from having the second-highest employment rate in the G7 in 2019 Q4 to having the fourth-highest employment rate in 2023 Q2, with Germany and Canada rising into second and third place. Looking at the OECD more widely, the UK has slipped from an impressive sixth place down to thirteenth place.

Read the full report HERE

Pdf 10 Pages