Wealth Check - What The New Government Needs To Know About Household Wealth As It Navigates The Challenges Ahead

29th July 2024

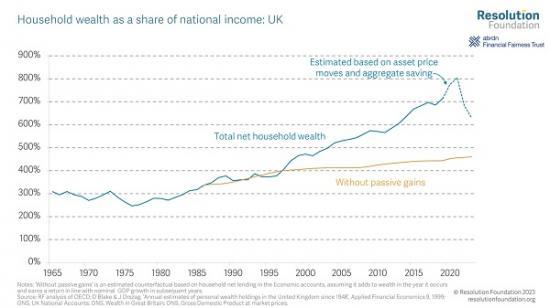

ritish household wealth has been on a rollercoaster ride in recent years. In Q1 2024, it was estimated to be worth more than six times GDP (630 per cent), more than 50 per cent higher than the last time Labour came into power (410 per cent in 1997).

The key driver of this huge rise in wealth is unearned passive gains. These gains have stretched the gap between the wealthy ‘haves' and the less fortunate ‘have nots': today, families in the top tenth of the wealth distribution have £1.3 million more in wealth per adult on average than those around the middle (fifth decile). Yet, despite huge increases in wealth, revenues raised from wealth-related taxes have barely moved, at around 3 per cent of GDP. Tapping unearned gains on wealth could be an appealing option for the Government, if it wants to avoid sharp cuts to some public services and maintain commitments not to raise the headline rates of taxes on income. To that end, reforms to Capital Gains Tax and Inheritance Tax could collectively raise almost £10 billion.

But not everyone has been able to join in on Britain's wealth boom. Historically low levels of active saving have left many families with small financial buffers. In June, three-in-ten Britons (27 per cent) said their household would be unable to cope with an unexpected bill of £850. Many workers are also failing to save enough in their pensions, despite the success of auto-enrolment during the 2010s. These two problems - of low precautionary savings today and insufficient pensions for the future - require a joined-up solution. For example, a higher default rate for auto-enrolled pension contributions could be coupled with contributions to a liquid ‘sidecar' savings account, which have been shown to boost precautionary savings for employees. The Government could complement this by expanding Help to Save, an existing scheme that incentivises saving for those on low incomes.

Household wealth in Britain now stands at more than six times national income, largely due to passive gains on existing wealth

The new Government faces no shortage of economic challenges. Public services are under severe pressure, while households are still recovering from a cost of living crisis that saw prices rise by 22 per cent in just two years, all against a backdrop of low wage growth and chronic under-saving. The Government will need to think carefully about policy to support household finances. And, on the back of the biggest tax-raising Parliament since the Second World War, it's time to reconsider the role of wealth taxes in today's system. On both fronts, it’s critical to understand the nature of household wealth in Britain today and its main drivers over the recent past.

In recent decades, Britain has lived through an unprecedented surge in the value of household wealth. As shown in Figure 1, when Labour last came into power, the combined wealth of British households was worth around four-times national income (410 per cent in 1997). Now, despite falling recently as global longer-term interest rates increased, it sits at more than six times national income (an estimated 630 per cent in Q1 2024) - in cash terms, this is an increase of £9.7 trillion.

This rise has led to big ‘wealth gaps’ in between British families, increasing the pounds and pence gaps between those at opposite ends of the wealth distribution, and making it harder to move up the wealth distribution by saving out of one’s own income. It also means a bigger role for gifts and inheritances - with the total value of the latter forecast to double over the next 20 years - something that undermines social mobility by tightening the link between people’s economic fortunes and those of their parents.

Britain’s wealth boom has been predominantly driven by ‘passive’ capital gains, rather than active saving. In particular, the period from the mid-1980s to the pandemic saw an unprecedented fall in global interest rates to near-zero levels. This pushed up the value of wealth, delivering large passive gains to those who owned wealth at the beginning of this period. The yellow line in Figure 1 shows an estimate for the value of UK household wealth in the absence of these extraordinary gains, where the value of accumulated financial assets grows in line with GDP. If this were the case, household wealth would be worth 4.5 times national income today, some £4.7 trillion less than its actual value in 2023.

Passive wealth gains haven’t shown up in tax revenues...

One might hope that huge passive gains from wealth would have brought with them higher tax revenues. Unfortunately, this hasn’t been the case. As shown in Figure 2, while household wealth more than doubled relative to national income over the past half-century, the revenues raised from wealth taxes have failed to follow suit. Although higher Capital Gains and Stamp Duty revenues have pushed revenues from wealth-related taxes to an all-time high in 2022 (3.4 per cent of GDP), this is far from a doubling (in 1972, revenues were 2.5 per cent of GDP).

Read the full report HERE

Pdf 10 Pages