What Are Fiscal Rules, Why Do We Have Them, And Could They Be Made Better?

17th October 2024

With the UK Budget approaching, speculation is mounting that Chancellor Rachel Reeves is considering changing the fiscal rules that the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) uses to assess whether the Government is meeting its budgetary targets. So it's worth thinking about how they have come about, and to what extent the rumoured changes are (i) sensible and (ii) likely to make a difference.

Why do we have fiscal rules?

Macroeconomists worry that fiscal policy suffers from what they call a ‘time inconsistency' problem. This means that what governments might see as their better option today might not be optimal in the long run. For example, a government close to an election might cut taxes or increase public spending in order to be re-elected, even if that causes public debt to increase faster or if it contributes to higher inflation by increasing aggregate demand at a time when such a stimulus isn't warranted.

To some extent, governments also suffer from the very human ‘time-preference' problem: we’d rather postpone painful decisions if we can, but if we do so indefinitely, it will eventually catch up with us. Why take unpopular decisions that make you less likely to hold on to power, only for the next government to benefit from them, as the Conservative Party found under John Major?[1]

Even if a looser fiscal policy might feel the path of least resistance at any point in time, persistent macroeconomic imbalances or unexpected increases in government borrowing with no plan for re-balancing the budget often do have very large and expensive consequences for the economy as a whole. There is extensive academic literature on the ‘deficit bias’, and how it can lead to poor economic outcomes, such as debt crises or slowdowns in growth.

But there are also solutions, which help navigate these issues to some extent.[2] As with all mechanisms designed to solve time inconsistency problems, they must tie the decision-makers’ hands to some extent by removing discretion - otherwise, they wouldn’t be an effective solution. Options include specific rules about how large the deficit or the level of public debt can be or having some sort of external assessment of whether these rules are being met. The UK has both, though they were introduced at different times.

A history of fiscal rules in the UK

Formal fiscal rules are a relatively recent innovation in the grand scheme of UK fiscal history, and date back to Gordon Brown’s appointment as Chancellor of the Exchequer in 1997.[3] Nevertheless, implicit or informal rules have guided policy for a long time. For example, prior to the Second World War, and with the exception of periods of international conflict, the government tried to achieve a balanced budget, and would adjust tax rates every year to achieve that. During the 19th century, it also attempted to reduce debt by a specified amount by having enough funds to repay it in net terms - something that we would today define as a primary surplus rule.

When Gordon Brown took office, two rules were introduced:

The ‘golden rule’, which stated that the current budget should be in balance over the economic cycle; and

The ‘sustainable investment rule’, which stated that the debt-to-GDP ratio should not average more than 40% over the economic cycle.

Apart from being misnomers - the golden rule in economics has to do with optimal economy-wide saving rather than the public finances, and the ‘sustainable investment rule’ had nothing directly to do with investment - these were also fairly murky rules. The economic cycle isn’t easy to date, with vintages of data and revisions changing our understanding of when the high and low points of GDP over a cycle took place. It also didn’t help that the UK doesn’t have a business cycle dating committee like the one in place in the US through the National Bureau of Economic Research. Looking back through the 1997 to 2009 budgets, one can find an ever-changing landscape of economic cycles, which the Treasury got to define to its own benefit.

For all their problems, the stability of these rules is quite remarkable relative to what came next. Some of this was due to the Great Financial Crisis – faced with such a large shock, the level at which rules were set looked impossible to achieve for a long time and attempting to do so would be counterproductive.

But there is a feeling that the first formal change was like letting the genie out of the bottle, and subsequent Chancellors have felt empowered to change them much more often. Contrast this with the 2% inflation rule that the Bank of England has had for the whole of that same period: even when it missed it by a large amount, that has been maintained and the Bank has instead signalled what it was doing to bring it back into balance. But perhaps that is the difference between a political position like that of Chancellor and the operationally independent Governor of the Bank.

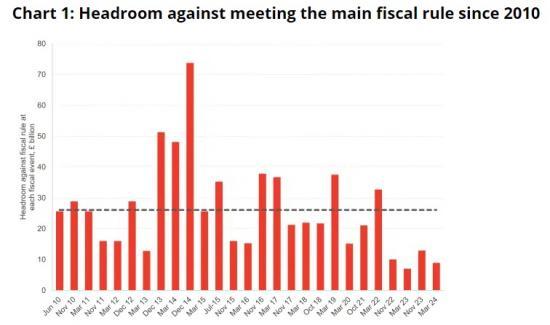

Since 2009, we are on our eighth set of fiscal rules, and Rachel Reeves has promised yet another one. All of these have generally measured sensible things[4] – the current budget deficit, the overall deficit, public sector net debt (including or excluding the Bank of England), the cyclically adjusted deficit – but the inability to stick to a set of rules has undoubtedly led to a loss of some of the confidence in their worth. After all, why should the next set be the right one if it changes every couple of years?

With the OBR into being in 2010, responsibility for assessing compliance with the fiscal rules was transferred to the nascent institution. This meant an improvement in transparency and in stringency of the rules, as no longer would some of the judgements made internally in the Treasury about the economic cycle or trend growth be allowed to sway the likelihood of the rules being met.

Before coming into Number 11, Rachel Reeves set out what she intended to install as her fiscal rules. In her Mais Lecture, delivered in March 2024, the then-Shadow Chancellor said that she would return to having the current budget in balance, and that debt would be falling in the final year of the forecast.

As we said before the election, the difference this will make in practice is immaterial – the debt rule is the binding constraint, and therefore if it remains in place (even if it’s the supplementary target), it will be what determines how much the Government can spend without the OBR deeming it to be failing to meet the fiscal rules. Removing the Bank of England/Central Government split might give the Chancellor some room for manoeuvre, but it would not be a massive game-changer.

‘Fiscal rule nutters’ and Goodhart’s law

When inflation targeting was becoming the norm, Mervyn King – later to become Governor of the Bank of England – worried about the possibility for an ‘inflation nutter’ – someone who only cared about bringing inflation to target without considering employment or GDP – being in charge of the central bank and the damage that could do to the economy.[5]

That has not come to pass, and central bankers have been much more flexible in their approach, being allowed the time and the discretion to change the speed at which inflation is adjusted back to target. This means that the inflation target has on many occasions been missed, but it still proves a useful anchor for where the Bank of England is headed. Crucially, the Bank has no qualms about forecasting that the target will not be hit in the forecast horizon, and does not feel compelled to set out an overly aggressive course of action just for the sake of hitting it.[6]

Perhaps one for the economics nerds but if you have gotten this far read on to the full report.

Read the full Fraser of Allender article HERE