The Increases In Scotland's Top Rate Of Income Tax May Have Reduced Revenues - Although Significant Uncertainty Remains

15th November 2024

Scotland's income tax rises have likely increased tax avoidance and migration - but the size of the effects is uncertain.

As well as setting spending plans, next month's Scottish Budget will also set the rates and bands of Scotland's devolved taxes for 2025-26. Moreover, alongside the Budget, the Scottish Government has said it will publish a tax strategy setting out its high-level approach to tax policymaking.

A key part of its strategy so far has been to increase the income tax paid by those with above-average incomes in order to raise revenue and increase the progressivity of the tax system. In the run-up to the Budget and tax strategy, where the Scottish Government faces a choice about whether to continue with this approach, it is worth asking: ‘What do we know about the impact of these changes?'.

Tax increases on higher earners amount to up to 7% of net income

The Scottish Government's income tax powers apply to income other than from savings and dividends (to which UK government tax rates still apply). It began to use its powers as soon as it could vary tax bands as well as existing tax rates in 2017-18:

It increased the higher-rate (40%) threshold by much less than the UK government did between 2017-18 and 2021-22.

It split the basic-rate (20%) band into starter-rate (19%), basic-rate (20%) and intermediate-rate (21%) bands, and increased the higher rate (from 40% to 41%) and top rate (from 45% to 46%) in 2018-19.

It further increased the higher rate (to 42%) and the top rate (to 47%) in 2023-24, while following a UK government decision to reduce the top tax threshold from £150,000 to £125,140.

It introduced a new ‘advanced' rate of 45% on incomes between £75,000 and £125,140, and again increased the top tax rate (to 48%) in 2024-25.

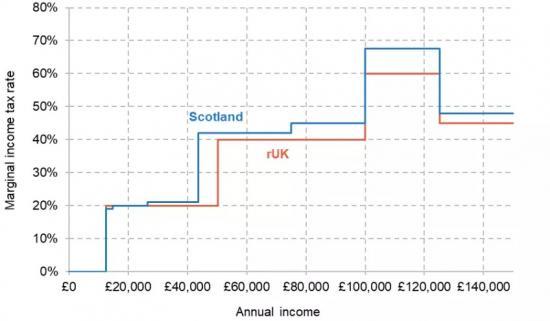

This has led to an increasingly complex income tax schedule in Scotland, with those with an annual income of more than £26,562 facing higher marginal tax rates than in the rest of the UK, as can be seen in Figure 1. The complexity introduced by having 19%, 20% and 21% is particularly unwarranted: for example, a small 0% band followed by a 21% band would be simpler and a little more progressive.

The higher marginal rates on income above £26,562 also mean that middle- and higher-income residents of Scotland pay more income tax than those in the rest of the UK (rUK), as illustrated in Figure 2.

A taxpayer with an income of £25,000 pays £23 a year less in Scotland than in rUK.

A taxpayer with an income of £50,000 pays £1,540 a year more in Scotland than in rUK, down from £1,552 last year, but up from £1,489 in 2022–23 and £830 in 2018–19.

A taxpayer with an income of £100,000 pays £3,346 more in Scotland than in rUK, up from £2,606 last year, £2,043 in 2022–23 and £1,330 in 2018–19.

The biggest proportional difference in income tax liability is for those near the threshold between the advanced and top tax bands. For example, a resident of Scotland pays £5,221 more tax than in rUK if their income is £125,000 – equivalent to a 7% reduction in after-tax income, up from about a 2% reduction in 2018–19, when tax policy first started to diverge notably.

Author

David Phillips - Associate Director of the Institute for Fiscal Studies

David is Head of Devolved and Local Government Finance. He also works on tax in developing countries as part of our TaxDev centre.

Read the full IFS article HERE