Taxes Are Going Up - Freeze On Allowances and Fiscal Drag

6th April 2025

April will bring a variety of changes in the tax system, ranging from wide-reaching to narrow impacts and from some that are very noticeable to others that are more subtle.

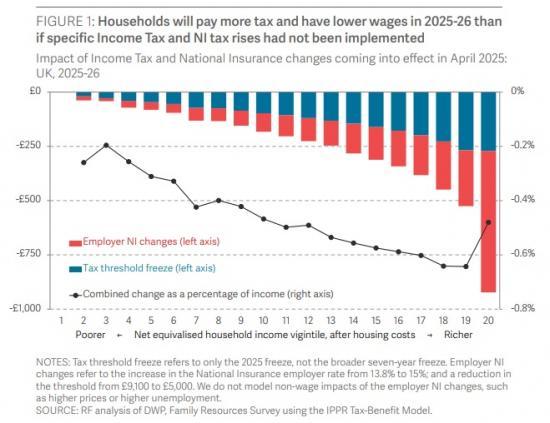

Although households won't observe any direct changes in their take-home pay due to tax changes in April, two tax rises are coming into effect this month that will ultimately affect their incomes, as Figure 1 shows. The newer tax rise is Rachel Reeves' changes to employer National Insurance (NI), announced at Autumn Budget 2024.

This £26 billion tax rise involves a higher rate of employer National Insurance (rising from 13.8 per cent to 15 per cent) and a lower threshold (reduced from £9,100 to £5,000 a year per job). The change in the threshold is also mitigated partially - and inefficiently - by an increase in the Employment Allowance, from £5,000 to £10,500 per firm.

Although employer NI is paid by employers, the incidence of the tax is expected to fall primarily on workers.

In Autumn Budget 2024, the OBR judged that 60 per cent of

the impact of the tax would result in lower real wages, while 40 per cent would be felt through lower profits in 2025-26. In Figure 1 we take into account the impact of the employer NI changes on wage growth which we assume to be 0.39 percentage points lower in 2025-26 than they would have been if the policy were not in place.

Low-paid jobs will be disproportionately affected by the employer NI changes, but the impact of both tax changes in household terms is relatively progressive, with the richest fifth of households losing 0.6 per cent of their disposable income as a result of these changes compared to 0.3 per cent for the poorest fifth (who receive a lower share of their income from earnings).

The other major income-related tax rise is the freezing again of the £12,570 personal allowance and the £50,270 higher rate threshold, originally scheduled by Rishi Sunak in Spring Budget 2021 as part of a five-year freeze (later extended for two years in Autumn Statement 2022).

Typically, these thresholds are uprated by the previous September's inflation, meaning if there were no threshold freeze, they would have been uprated by 1.7 per cent. As a result, most working basic-rate payers will lose £60 this year due to the threshold freeze compared to default uprating, while higher-rate payers will generally lose £200.

Although these are notable impacts, September's low inflation rate means that the losses are smaller than they could have been - and much lower than in some previous years.

Altogether, the threshold freeze and the wage impact of the employer NI rise are estimated to lower the median household's income by £170 relative to an all-else-equal world of no tax rises (although such a world would of course have required different choices to be made on other taxes or public spending that might have reduced living standards in other ways).

A range of other tax rises will also kick in this April, but will not be as broadly felt:

including the expiration of the temporary Stamp Duty cut; higher Vehicle Excise Duty,

including for the first time electric vehicles; some Capital Gains Tax reforms from the Autumn Budget; and changes in business rates.

Council Tax rises, however, will be evident for almost every household across the UK, given that it is paid in a similar way to a bill, making it more noticeable than payroll taxes.

Across England, increases are capped at 4.99 per cent in most local authorities and most have made full use of that option, resulting in the average Band D rate rising by £109 this year.

Some councils in England have had special permission to increase Council Tax by more than this, with the largest increase being in Bradford, where Council Tax has risen by 10 per cent.

In Scotland, levels are increasing by 9 per cent on average, or £117, following a period of successive freezes or capped increases.

In Wales, they are increasing by an average of 7 per cent, or £145 for Band D properties.

And in Northern Ireland bills under the separate domestic rating system will be rising by almost 5 per cent on average.

Stepping back, there is also a broader trend of Council Tax rising in significance for households and the Exchequer. The ratio of Council Tax to GDP is now at its highest yet

outside of the pandemic (where the ratio was artificially high because GDP fell during the periods of lockdown), having risen from 1.0 per cent in 1994-95 to 1.5 per cent in 2015-16, 1.7 per cent now and a projected 1.8 per cent by 2029-30.

Between 2023-24 and 2029-30, real Council Tax revenue is set to rise by around £9 billion, or roughly £300 per household.

A rise in property taxation is not necessarily a bad thing. Recurring property taxes are considered to be among the least economically harmful.12 And - to the debateable extent that Council Tax is a property tax - its incidence may ultimately be felt through lower property prices or rents (although this link is more complicated in the case of social housing, where rents cannot freely adjust).

However, the tax's growing importance makes it ever-more important that it be well designed in terms of efficiency, regional fairness

and within-region fairness, and arguably Council Tax fails on all of those counts.

Reform is therefore needed in every nation of Great Britain.

Read the full Resolution Foundation report HERE