The good, the bad and the messy - Responding to the Pathways to Work Green Paper consultation

1st July 2025

This week marks an important moment for this Government's welfare reform plans: as Parliament prepares to vote on major legislation to make cuts to PIP and UC-Health, the consultation on longer-term changes to the benefits system, set out in the Pathways to Work Green Paper, also closes.

There are some good proposals included in the Green Paper: most notably, the Government plans to introduce a new unemployment insurance scheme.

If properly implemented, this would improve income protection for workers who experience unemployment, while also boosting dynamism and growth. But the Government should think carefully about its plans to create a single benefit for both jobseekers and those out of work due to poor health: this would significantly reduce support for people who have to leave work due to ill health.

On the other hand, the proposal to remove UC-Health from under-22s is poorly thought through. While the prevalence of ill health, and claims for disability benefits like PIP, are rising among young people aged 16-21, claims for incapacity benefits like UC-Health are not. Rather than cutting UC-Health support for this age group, the Government should prioritise boosting access to employment and educational support.

Finally, putting the wide-ranging suite of benefit changes included in the Green Paper into practice is likely to become messy. Scrapping the Work Capability Assessment would be a generational change to the health-related benefits system, not just a change to the way that assessments are carried out. The problems it throws up are not ones that can be patched over by making exceptions for a small group of claimants, and it deserves greater attention.

As well as making changes to PIP and UC-Health via Primary Legislation, the Government is also consulting on a package of longer-term welfare reforms

As the Universal Credit and Personal Independence Payment Bill continues its rocky journey through Parliament, the focus has understandably been on the changes to the eligibility for and rates of health- and disability-related benefits that it introduces. The Government will be hoping that the latest concessions allow it to progress that legislation through Parliament tomorrow.

But at the same time, the Government's consultation on other aspects of its ‘Pathways to Work' Green Paper closes today. In this Spotlight, we focus on the elements of the Green Paper that the Government is formally consulting on and that are outside the scope of this week's Bill: these are a range of longer-term changes to the benefits system that the Government could enact later this Parliament.[1]

The good: introducing a new Unemployment Insurance scheme

The Government is consulting on reforming the few remaining contributory benefits and introducing a new ‘Unemployment Insurance' scheme instead, replacing contributory Jobseeker’s Allowance (JSA) and Employment and Support Allowance (ESA). The proposals would lead to a more generous system of unemployment insurance, but a less generous form of sickness insurance, and I consider both below.

As set out in previous Resolution Foundation work, the current social security system fails to offer adequate income protection to workers across the income distribution, in the most part because the flat-rate Contributory JSA and the basic allowance in Universal Credit are both worth just £92.05 a week in 2025-26. This problem has gotten worse over time: these unemployment benefits are now worth just 14 per cent of average weekly earnings, down from 24 per cent four decades ago. The replacement rate in the UK for a single earner on an average wage who experiences unemployment is among the lowest in the OECD.

Creating a more generous, but time-limited, form of unemployment insurance would be a good move. This would better protect workers’ living standards if they are hit by unemployment, but it could also contribute to greater dynamism and therefore growth. More generous unemployment insurance schemes tend to support workers to find better-paid and longer-lasting jobs, and by reducing the fear of not being able to meet financial obligations in the event of unemployment, workers can feel more confident in taking risky job moves.

There are two key design parameters for an unemployment insurance scheme: generosity, and duration.[2] The Government has proposed setting this new benefit at the current level of benefits for those not working due to ill health (in 2025-26, this is £140.55 per week). This would be an improvement on the current system, and would mean that jobseekers would see their level of support increase by half (an increase of £48.50 per week, or 53 per cent). But we recommend that the Government goes further and introduces a form of unemployment insurance that is linked to workers’ previous wages: in our view, this should follow the old Job Retention (furlough) Scheme, and be paid at 65 per cent of previous wages, up to a cap set at median earnings. This would lead to a maximum payment of £378 per week in 2025-26.

Second, we suggest that this new unemployment insurance should only be paid for short durations of time: in normal economic times, we recommend a duration of three months. This strikes a balance between protecting workers’ living standards while they look for a job, and minimising the ‘moral hazard’ issue - where reduced work incentives lead to unduly long spells of unemployment.[3] And a new unemployment insurance system should be designed flexibly: during recessions, or other times when it would be unreasonable to expect workers to find employment within three months, unemployment insurance should be paid for a longer time.

Introducing a more generous, but time-limited, unemployment insurance scheme would be relatively inexpensive at the moment, reflecting current patterns of low unemployment, and the fact that the benefit would only be paid for periods of three months. Our previous estimate was that such a scheme would cost £0.4 billion per year in spells of low unemployment, rising to £1.1 billion per year in a period of high unemployment (or £2.6 billion if the payment duration was extended to six months), all in 2024-25 prices.

But, as mentioned above, the Government appears to be proposing adopting the same benefit for people who are unemployed and those who have to stop working due to ill health. It seems to be little understood that moving to a unified, time-limited, ‘unemployment’ insurance scheme for those who are both unemployed and out of work due to ill health would be a cut to the amount of contributory benefits paid to ill and disabled people (continuing the erosion of the role of contributory benefits in insuring people against illness). Currently, contributory ESA can be paid indefinitely for those with severe barriers to work who are place in the ‘Support Group’. There are 671,000 people in this category at present, two-fifths of whom (257,000) are only receiving contributory ESA, rather than getting income-based ESA or Universal Credit as well. This group would lose support under the Government’s proposals to create a time-limited unemployment insurance scheme, which would be a major change to what the state offers people from middle-and-higher-income families who have to leave work due to ill health. The current system is sensible in treating people who are unemployed differently from people who cannot work through ill health - for example, the evidence that leads us to favour a short duration of unemployment insurance does not apply to providing sickness insurance - and so it is not clear that moving to a single benefit providing income insurance in these very different circumstances is necessarily a positive step.

The bad: removing access to the health element of Universal Credit for adults aged under 22

The Government is also consulting on delaying access to the health element of Universal Credit (UC-Health) until people turn 22, meaning that young people aged 16-21 would lose access to this health top-up. In the latest data from March 2025, there were 72,000 young people aged 16-21 receiving the UC-Health top-up (the ‘LCWRA’ element). For young people like these making claims from next year, their UC income would be reduced by 39 per cent, or £217 per month, if they were no longer eligible for the LCWRA element.

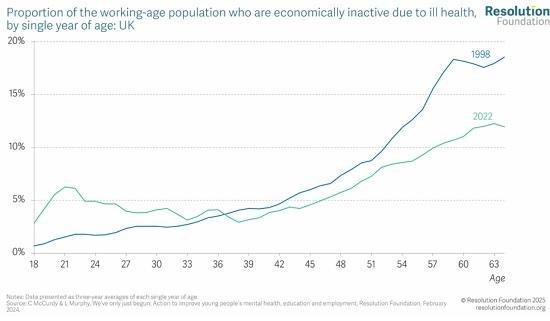

The Government is right to acknowledge that there is a particular problem of rising ill health among young people which is feeding through to adverse educational and employment outcomes. The number of young people aged 18-24 who are economically inactive due to ill health has doubled in the decade between 2013 and 2023, reaching 190,000 people. Those in their early twenties are now more likely to be economically inactive due to ill health than those in their early forties (see Figure 1).

Read he full report HERE