Jeremy Hunt's Smooth(ing) Budget

16th February 2023

A month today Jeremy Hunt will deliver his first Budget. It's shaping up to be a calmer affair than last Autumn's repeated emergency fiscal announcements. Then again almost anything would.

That air of normality extends to plans to use the Budget to focus on longer-term questions, specifically how to get more people working and the economy growing. But planning a more ‘normal' Budget, doesn't mean anything about the current economic situation is normal.

Whatever Westminster wants to talk about, the cost-of-living crisis is the backdrop to this Budget, and is where families are focused. So, despite headlines saying "Energy bills extra support ruled out by chancellor", the Chancellor will have more to say on the topic. Here's why, and what that is likely to be.

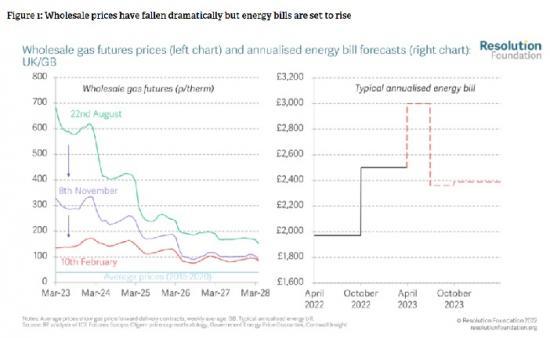

The big energy news of recent months is good news: European wholesale gas prices for 2023-24 are down 75 per cent since from their summer peak, and 50 per cent since the Chancellor’s Autumn Statement. This is incredibly welcome - reducing the risk, or at least depth, of a 2023 recession.

But it creates a challenge when combined with the timing of Treasury measures to reduce energy support: a rollercoaster for household bills, rising from the equivalent of an annualised £2,500 for a typical bill today to £3,000 in April, before falling back to a little below £2,400 from July.

This rollercoaster makes little sense. The point of government policy during this crisis has been to smooth consumers through the worst of the energy price shock (the case for which is strengthened by the fact that we have now learnt that much of the increase is likely to be temporary). But now policy isn’t smoothing prices, it’s causing the spike.

For customers who pay their bills by direct debits, their payment method will smooth out payments even if policy makers fail to smooth out energy costs this spring. But the most acute problem is for those on pre-payment meters (PPM), whose payments are not smoothed at all and will have to find almost £250 in cash for April’s bill alone.

In fact, the bill increases in April will be even starker as the £400 universal payments (the Energy Bills Discount) also come to an end then. Even as temperatures rise and energy usage falls, this means typical PPM customer monthly bills are on course to rise by 22 per cent from March to April (from £202 to £247).

The solution is pretty obvious. The Treasury can - and almost certainly will - delay the increase in EPG for three months to give wholesale prices time to feed through.

This will have a price tag, increasing the cost of the EPG next year from £1.5 billion to £4.5 billion.[1] A £3 billion increase is significant, but still leaves more significant savings compared to the expected cost of £12.8 billion at the time of the Autumn Statement. Put it this way: falling wholesale prices knocked 90 per cent off the estimated cost of the EPG next year. Even if the Chancellor chooses to iron this temporary bill rise out, the cost of the EPG in 2023-24 will still have fallen by around two-thirds (65 per cent) since last November.

The Treasury will be content to live with this because the cost is clearly temporary, with no impact on their central fiscal rule to have "debt falling in the medium term" or their ongoing exposure to wholesale gas price movements.

The Bank of England will be actively keen too, with the coming spike in energy bills in April at risk of slowing the pace of inflation falls this year. Smoothing the spike out will bring inflation down by 1 percentage point in April from where it would otherwise be, as the next chart shows. This would accelerate current falls in inflation (even though it won’t change inflation’s underlying trajectory, and will have an offsetting temporary upward pressure on inflation in the second quarter of 2024). Based on the Bank of England’s inflation forecast, inflation in the second quarter of 2023 would be 7.5 per cent without the energy cost spoke, compared to 8.4 per cent on current plans.

Note

Plenty more in the full article. Read it HERE