How Important Are Defined Contribution Pensions For Financing Retirement?

30th June 2023

The demise of traditional defined benefit pension plans (which provide a guaranteed income from retirement to death) and the abolition of near-compulsory annuitisation of defined contribution pensions in 2015 has led to increasing interest. Or even concern, around how people access their defined contribution (DC) pension wealth.

Using microdata on households' wealth, this report provides new evidence on:

the importance of DC pension wealth in household wealth portfolios for those approaching retirement;

how that is likely to change as subsequent generations approach retirement;

the extent to which individuals in their 50s and early 60s have a plan on how to access their DC pension wealth;

which people are particularly likely to withdraw funds from their pension in one go.

Key findings

1. Close to half of working-age people have at least a small amount of wealth held in defined contribution (DC) pensions. Among those aged 25-59, this is true of 46% of individuals and 64% of households. Wealthier people are more likely to have DC pension wealth: 60% of individuals in the top tenth of the (non-pension) wealth distribution have DC pension wealth, compared with 32% of those in the bottom tenth.

2. Just over three-quarters (76%) of individuals aged 50-59 - those approaching retirement - have some private pension wealth. Half of this age group (50%) have some DC wealth, and a little under half (43%) have a defined benefit (DB) pension. One in six (17%) hold wealth in both DC and DB pensions. This means that a third (33%) of those approaching retirement with DC wealth also have a DB pension.

3. People hold - on average - considerably less wealth in DC pensions than in traditional DB pensions. The median (middle) value of DC pension pots among those aged 50-59 with a DC pension was £33,500 in 2018-20, compared with around £220,500 for the estimated value of the median (middle) DB pension promise for those with DB pensions. Amongst families with at least some DC pension wealth, it is worth - on average - 12% of family wealth once we include the value of housing, the state pension, and other pensions and savings. This compares with large fractions of wealth on average being held in annuitised forms or housing (24% in the state pension, 19% in DB pensions and 24% in main property).

4. DC pension wealth is increasing significantly over time. Successive generations of people are increasingly likely to have saved in a DC pension as a result of the demise of DB pensions in the private sector and the introduction of automatic enrolment into workplace pensions. For example, in their mid 40s, 49% of people born in the mid 1970s had some savings in a DC pension plan, compared with 37% of people born in the mid 1960s at the same age. Younger age groups are also less likely to be actively saving in a DB pension scheme than current older workers.

5. People in their 50s with higher levels of overall wealth also tend to have greater amounts of DC pension wealth. This means that the decisions made over how to access DC wealth will matter most to richer people. People with low levels of wealth typically have so little accumulated DC pension wealth that however they withdraw it, it is unlikely to make a meaningful difference to their standard of living over the course of their retirement. On the other hand, people with very high levels of wealth tend to also have significant amounts of other wealth available to support them in retirement. Thus it is those around the middle or the upper middle of the wealth distribution for whom the decisions over how to access private pension wealth are going to be most consequential. There are a range of factors that people will need to take into account when deciding how to draw their DC pension wealth, but the key decision will be the extent to which people want to trade off flexibility (by withdrawing chunks of cash or using ‘flexi-access drawdown') against the security and certainty provided by an annuity.

6. More than four in ten people in their 50s and early 60s who have savings in a DC pension do not know how they plan to access their pensions. This is more likely among those with low levels of wealth, even after controlling for other observed characteristics. Those in paid work and those who have not used a financial adviser are also less likely to have plans for how to access their DC pension pots. Those who can answer more financial literacy questions correctly and those who are owner-occupiers are relatively more likely to plan on buying an annuity rather than accessing their pension savings more flexibly.

7. Administrative data show that a large majority of people accessing DC pension plans withdraw the pot in full. This leads to concerns that some might be spending their retirement resources too quickly. But it is important to take into account wider financial resources, especially those that are already in annuitised forms. Even fully drawn DC pension pots - which on average are worth around £22,600 - typically make up a small fraction of overall resources. At the median, the withdrawn funds account for only 3.1% of private family wealth.

8. However, a minority of people make large withdrawals from their pension pots that make up a large fraction of household resources. For one in six of those who took out a DC pot in full, the amount withdrawn was at least £20,000 and made up at least a tenth of their overall family wealth.

9. A key policy challenge is identifying those for whom the decisions around DC pension decumulation are most important. Policymakers should aim to target support at those who are at the biggest risk of making imprudent financial decisions which could materially affect their standard of living in retirement. At a minimum, the Pensions Dashboard could - in time - provide some help in allowing people to understand and visualise the different pension savings they have. But more broadly, people should think of their pension savings in the context of their housing, other savings, and their partner's/spouse's pension wealth and other savings too. Default decumulation pathways should be considered, alongside a framework for decision-making that lays out the key trade-offs clearly to help people achieve good outcomes. Impartial and free pensions guidance through Pension Wise is already available, but take-up is currently very low. And even those who access this guidance usually only do so at a stage when they are accessing their DC pot for the first time, rather than getting support with planning for retirement earlier on. Expanding take-up of Pension Wise advice could be one way in which more support could be provided, although ensuring that the standards and quality of this guidance remain high is important.

10. As the importance of DC pots as a proportion of wealth is increasing over time, future generations will be more reliant on DC schemes and less reliant on (annuitised) DB schemes. While for many of those currently approaching retirement the decisions around accessing DC pots are ‘low-stakes' because of other resources available to them, future generations will rely more heavily on DC pots for financing their retirement. The risks around making decisions that have adverse and long-run consequences will grow over time as the prevalence and size of average DC pots start growing. This is why the time for designing policies to help individuals who rely on DC pots for financing their retirement is now, so that future generations will be protected against adverse outcomes at older ages.

1. Introduction

‘Pension freedoms' - or more formally the end of near-compulsory annuitisation of defined contribution (DC) pension wealth introduced in the UK in 2015 – have given individuals considerably more flexibility over when, and how, to access DC pension wealth. Since the announcement of this policy, annuity purchases have collapsed and even the increases in interest rates (and therefore annuity rates) since early 2022 have only led to a very limited increase in the number of annuity purchases.

Discussion about the benefits – and disadvantages – of the introduction of pension freedoms often focuses on the trade-offs between flexibility and risk. Individuals approaching retirement have more choice and freedom to draw on their DC pension savings in ways that are appropriate for their spending needs and they do not have to lock in – at a single point in time – annuity rates many saw as poor value. On the other hand, concerns have been expressed about the difficulties individuals face in retirement income planning, given uncertain (and potentially misperceived) life expectancy, low financial literacy, limited engagement with pensions, and low take-up of regulated financial advice (Adams and Ernstsone, 2018). Pensioners therefore risk drawing down on their private resources too fast – leaving them with little other than their housing and state support – or too slowly resulting in a needlessly frugal retirement.

However, the importance of the decisions that people take regarding their defined contribution pension wealth around retirement is ultimately determined by not just the amount of DC wealth they have but also the other assets in their, and their spouse's (if they have one), portfolio(s). For some, the decisions regarding their DC pension wealth will be ‘low-stakes' decisions, particularly if the accumulated pots are small or if sizeable other resources are available. And the value to individuals of additional longevity insurance provided by annuities may be limited, especially if large fractions of their portfolio are already held in annuitised forms, most notably entitlements to the state pension, defined benefit pension wealth, and the consumption flow provided to households by owner-occupied housing. That being said, with most retirement resources previously held in annuitised forms, the increase in non-annuitised wealth for retirees implies people are bearing more financial risk related to their life expectancy (‘longevity risk') than previous generations of people approaching retirement, and some will have to make decisions throughout their retirement over the extent to which they should be drawing on their pension pots.

This report sheds light on these issues by examining the wealth portfolios of those approaching retirement. A particular advantage of the data we use in most of this analysis – the UK's Wealth and Assets Survey (WAS) – is that we observe information on all the assets held by all members of the households. This includes all pension wealth as well as housing and other wealth. In addition to detailed data on wealth portfolios, the data contain specific questions on how individuals plan to access, and have accessed, DC pension wealth. With data on younger individuals too, who are not yet approaching retirement, we are also able to think about how pension freedoms may differentially affect subsequent generations.

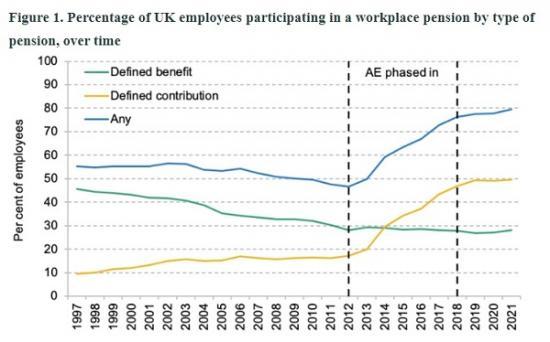

To provide background to this issue, Figure 1 illustrates a key change in the UK pensions landscape over the last 25 years. The late 1990s and 2000s saw large declines in defined benefit (also known as final salary schemes) pension provision, with smaller growth in defined contribution provision. Following the phased introduction of automatic enrolment (AE) starting in 2012, pension participation jumped dramatically, driven entirely by defined contribution arrangements. In 2021, half of all employees were contributing to a defined contribution pension plan, though still almost three in ten were contributing to defined benefit plans (mostly in the public sector, with only around one in ten private sector employees in defined benefit (DB) schemes – see Cribb et al. (2023)). The decline of DB arrangements and rise of DC participation following automatic enrolment means that there are many more people with DC pension wealth than 25 years ago, and many more, often very small, pension pots.

Read the full report HERE

Pension Calculator Forecast

https://www.moneyhelper.org.uk/en/pensions-and-retirement/pensions-basics/pension-calculator