Rates Of Change - The Impact Of A Below-inflation Uprating On Working-age Benefits

15th October 2023

Next week will see the publication of September's inflation figure, the basis on which key working-age benefits are normally uprated in the following April. But with the public finances under real pressure, and prices expected to fall in the coming months, there are signs the Government is considering a departure from standard practice by under-indexing key working-age benefits in 2024-25.

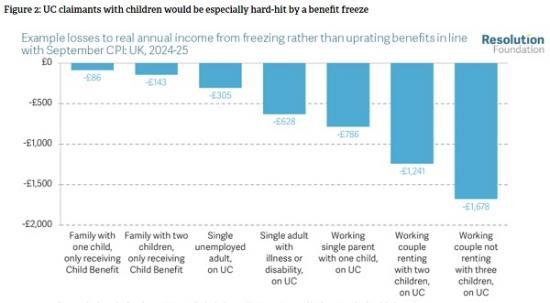

This would be a very bad idea indeed. A decision not to uprate working-age benefits in line with inflation would affect more than four-in-ten (9 million) working-age households in the UK. And the losses for many would be material: if key benefits were frozen, a single adult working at least 20 hours a week at minimum wage with an illness or disability claiming UC would see their annual income fall by £628, for example; a working couple with two children on UC earning the same would experience a £1,241 shortfall over the course of the year; and a similar working couple with three children in receipt of UC would suffer a dramatic £1,678 fall to their income next fiscal year.

Freezing benefits in 2024-25 would drive up inequality and impoverish many: 400,000 more children would grow up in poverty next year as a result. Some may argue that this approach is needed to ‘correct' for the ‘generous' uprating decision of last autumn, but this is wrong: if working-age benefits were uprated next April in line with September's inflation figure, they would still only return to the real value they had on the eve of the pandemic.

Rishi Sunak has shown a marked appetite in recent weeks for taking ‘difficult' decisions - and all the more so if they save significant amounts of money in these straitened times. So, could another such decision be in the Government's sights? Next Wednesday (18 October) will see the publication of September’s annual inflation figure, a critical number not just because it has implications for future interest rates, but also because it is the basis on which most working-age benefits should be uprated in April 2024. Inflation is expected to be far lower than last year: the most recent forecast from the Bank of England is that CPI will stand at 6.9 per cent for the third quarter of 2023, compared to 10.1 per cent in September 2022. Nonetheless, there are signs that the Government is considering under-indexing working-age benefits next year, in contrast to the principled approach it took last autumn.[1]

Why might it choose to adopt such a strategy? The answer to that question is simple: uprating decisions can save the Government a huge amount of money, especially when inflation is riding high. If Universal Credit (UC) rates were frozen (the most extreme scenario) rather than uprated by 6.9 per cent in April 2024, for example, this would save the Treasury £2.9 billion in 2024-25 alone (savings, of course, would also accrue in future years unless the benefit was over-indexed at some later point).[2] Likewise, freezing the value of all other ‘non-protected’ working-age benefits such as Child Benefit (CB) , tax credits, Job Seekers Allowance (JSA), Statutory Maternity and Paternity Pay (SMP/SPP) and Maternity Allowance (MA) would bring in a further £1.3 billion in 2024-25.[3] With the costs of servicing public debt at a near all-time high, this £4.2 billion of savings would be very welcome indeed.[4]

But savings to Government are losses to families who are in receipt of benefits, and Figure 1 shows how widespread shortfalls would be. More than four-in-ten (45 per cent) working-age households would see a drop in their real income as a result of a benefit freeze in April 2024, equivalent to over 9 million households. That figure rises to more than six-in-ten (62 per cent) households where at least one member has a disability (4.4 million households); seven-in-ten (73 per cent) couples with children (4.2 million households) and more than nine-in-ten (93 per cent) single parents (1.7 million households).[5] Strikingly, one-third (32 per cent) of households where all adults are in work would also face a fall in real income in the event of a benefit freeze next year.

Moreover, as Figure 1 also shows, for many households the losses would be material. We estimate that half (52 per cent) of the households who would lose were working-age benefits frozen in April 2024 would see their annual income fall by £500 or more (4.7 million households in all). And for some family types, the share affected experiencing a large-scale income loss is higher still: 1.4 million single parent households would see their annual income fall in real terms but £500 or more, for example (84 per cent of all those affected); 3.2 million households containing at least one member with a disability would be equally hard-hit (72 per cent of all those affected); and likewise 1.4 million households where at least one member is in work (33 per cent of all those affected).

Figure 2 drives home the gravity of the income hit for some family types in the event of a benefit freeze. A household with two children in receipt of Child Benefit only would experience a real-term loss of £143 over the course of 2024-25 if benefits were to be frozen, for example. But a single adult with an illness or disability claiming UC would see their annual income fall by £628, more than four-times that amount; a working couple with two children on UC would experience a £1,241 shortfall over the course of the year, eight-times more than the family claiming Child Benefit only; and a working couple in receipt of UC with three children (all born before April 2017 and therefore not affected by the 2-child limit) would suffer a dramatic £1,678 fall in their annual income, a hit almost twelve-times as large as a two-child family in receipt of Child Benefit alone.[6]

Read the full report HERE

Pdf 7 Pages

The graphs are much clearer in the Pdf file.