Policy Risks To The Fiscal Outlook

19th October 2023

Pressures on both revenue and spending are skewed to add to borrowing over the next few years, and threaten the ‘centrality' of official forecasts.

1 Under the March 2023 Budget forecast, debt was forecast to stabilise at the end of the forecast horizon, leaving no scope for additional borrowing under the government's current set of fiscal rules. But pressures on both revenue and spending are skewed to add to borrowing over the next few years, unless difficult decisions are made on spending cuts or tax rises.

2 Perhaps the most obvious risk to the current forecast is that the government has a stated indexation policy for fuel duties that stretches credulity to breaking point. Successive freezes that can be predicted in advance are in fact worse than a stated policy of non-indexation: we not only incur substantial costs to the public finances but the official forecast, for which the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) takes stated policy as given, is made less credible. Freezing fuel duties at their current rates - as the government surely intends - would reduce forecast revenues in 2027-28 by £6 billion. This and other known pressures that the OBR is nevertheless unable to include in its forecast mean the official forecast is not as ‘central' as it should be. This is harmful for transparency and makes scrutiny of fiscal plans more difficult.

3 A further fiscal risk comes from the Chancellor's new corporation tax full-expensing policy. This has been put in place for three years (2023-24, 2024-25 and 2025-26), adding around £10 billion a year to measured borrowing in those years. Jeremy Hunt has signalled his desire for it to be made permanent. The OBR has said that it could cost approaching £10 billion a year to do this. Making full expensing permanent would add to borrowing from March 2026, but, as stated in Chapter 10, a better estimate of the eventual direct fiscal cost would be around £1–3 billion a year.

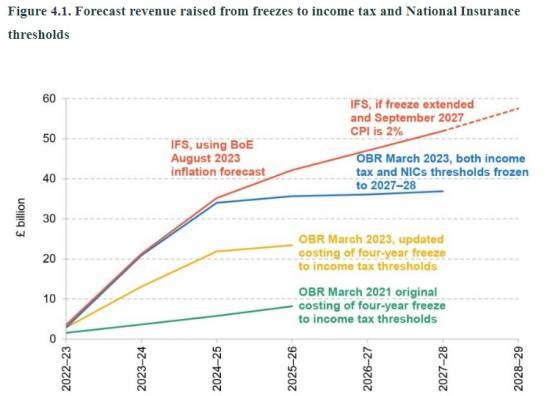

4 In an environment of high and volatile inflation, cash-terms freezes to income tax and National Insurance thresholds are now set to raise much more than expected just months ago. An up-to-date inflation forecast suggests they could raise £52 billion in 2027–28 (or £43 billion if we include the cost of the big July 2022 uplift in the point at which employees and the self-employed pay National Insurance contributions, from which the level is now frozen). This is 40% more than the OBR's March 2023 forecast and 6½ times as much as the original package of threshold freezes was expected to raise when announced in March 2021 (£8 billion). As perhaps could have been predicted, it means much of the large increase in the personal allowance implemented during the 2010s has not proven to be sustainable: the freeze could reverse two-thirds of that increase. It could also lead to a record two-thirds of adults paying income tax (and a record one-sixth of adults paying higher-rate tax). This large increase in taxpayer numbers could lead to pressure on the Chancellor, or his successor, to end the planned six-year freeze – much longer than any previously attempted or delivered – early.

5 Provisional spending totals beyond 2025 pencil in a 1% real-terms increase in day-to-day spending on public services each year. These spending plans are far tighter than those bequeathed by then Chancellor Rishi Sunak, implying around £15 billion less spending in 2027–28 than set out in his 2022 Spring Statement, and seem incompatible with the government's – or for that matter the Labour opposition's – appetite to spend. After taking account of commitments on the NHS workforce, the huge expansion of state-funded early-years childcare announced in the Budget, increased spending on defence and overseas aid (to meet stated commitments) and a likely protection of school budgets, ‘unprotected’ departments would need to shoulder cuts of 1.5% per year, or £9.4 billion in today’s terms, by 2027–28. Mr Hunt has also lowered planned spending on investment, with the size of this cut relative to the spending implied by the previous plans bequeathed by Mr Sunak rising to £13 billion in 2027–28.

6 Longer-term structural factors – for example, the ageing of the population and cost pressures on the health and social care budgets – also challenge the sustainability of the public finances. The OBR projects that spending on state pensions and health and social care will increase by 5% of national income – equivalent to £137 billion a year in today’s terms – up to 2050 and then continue rising. Accommodating these spending pressures would require deep cuts to spending elsewhere or a big further increase in tax.

7 There is inherent uncertainty around these long-run projections. On the one hand, there has been a significant increase in net immigration and slowing increases in life expectancy at older ages, both of which will ease some of the pressure on the public finances in the long term. On the other hand, steadily declining fertility rates will make it harder to finance growing ageing-related spending, over and above the latest OBR projections, as they will reduce the population of working-age adults in coming decades.

8 Long-term public finances challenges around ageing, health and social care, and the transition to net zero have been known about for years, but there is a temptation to always push addressing these issues to ‘tomorrow’ – or just beyond the reach of the current forecast horizon and specific fiscal targets. However, many of the effects of an ageing population are already showing today and will only become more pressing over coming decades. A detailed and coherent government strategy for tackling these pressures is urgently needed.

4.1 Introduction

Under the Office for Budget Responsibility’s March 2023 Budget forecast, the Chancellor was only meeting his commitment to have debt as a share of national income falling at the end of the forecast period by a hair’s breadth. This forecast is intended to reflect a ‘central’ expectation of how the public finances might evolve under current plans. In this chapter, we set out a number of policy issues that put pressure on this forecast and act as a threat to its ‘centrality’. Some areas, notably spending on incapacity and disability benefits, introduce genuine two-sided uncertainty – in other words, costs to the public finances, while very uncertain, might plausibly turn out either substantially higher or substantially lower than currently forecast. But most of them are pressures that appear likely to increase spending and reduce revenues, rather than the other way around. Furthermore, few of these pressures are temporary in nature. Additional borrowing to address them would therefore likely be permanent and would not be likely to be consistent with the government’s stated fiscal objectives.

The rest of this chapter proceeds as follows. First, we discuss risks to tax revenues, starting with the ongoing freeze to direct personal tax thresholds (Section 4.2) and moving on to full-expensing capital allowances (Section 4.3) and successive ‘temporary’ fuel duty freezes and cuts (Section 4.4). We then move on to spending, discussing spending plans for public services (Section 4.5), spending on benefits to support disabled people and those with health conditions (Section 4.6) and spending on support for housing costs (Section 4.7). We then consider the longer-term pressures on health and social care and pensions, including a comparison of how the UK’s long-term fiscal challenge compares with that faced in other countries (Section 4.8). In the final section, we offer some general recommendations on what all these challenges mean for the forthcoming Autumn Statement and beyond.

4.2 Freezes to direct personal tax thresholds

Rather than increasing each year in line with inflation (as measured by the CPI), which is the usual default, most direct tax thresholds in the personal tax system have been frozen in cash terms since at least April 2021. By far the most significant of these (in terms of the number of people affected and the resulting revenue raised) are the freezes to the income tax personal allowance. Rishi Sunak, as Chancellor, announced in his March 2021 Budget that this would be frozen at its 2021–22 level for four years (2022–23, 2023–24, 2024–25 and 2025–26). The same would hold for the income tax higher-rate threshold (and the upper earnings limit (UEL) in National Insurance contributions (NICs)). In his Autumn Statement of 2022, Jeremy Hunt – Mr Sunak’s successor but two as Chancellor – extended this for an additional two years, so it is now set to cover both 2026–27 and 2027–28 and run for a six-year period in total.

Alongside these freezes in income tax thresholds, the point at which employee and self-employed NICs start to be paid was increased by Mr Sunak in the 2022 Spring Statement to align them with the income tax personal allowance. Over the nine months from July 2022 to March 2023, this was costed by HM Treasury as a £6.3 billion tax cut (implying £8.4 billion over a 12-month period). But these thresholds – as they are aligned with the personal allowance – are now frozen. And in the Autumn Statement of 2022, Mr Hunt also extended the freeze to the point at which employer NICs start to be paid, which is another tax-raising measure. Under current policy, therefore, all of these thresholds are to remain at their current cash levels through to 2027–28.

Freezing these thresholds means they are less generous than if they were indexed in line with inflation, and the measure therefore brings in more revenue. The amounts raised by the decision to freeze will depend considerably on the rate of inflation: lower inflation would mean that a policy of freezing an allowance delivered a smaller tax rise. So the current period of high inflation means that more is raised – and the fact that inflation is much higher than was forecast when the freezes were announced means that more will be raised than was expected at the time of the original announcement.

[b]How much revenue might the freeze raise?

Different forecast vintages for the revenue raised from this package of measures are shown in Figure 4.1. The March 2021 Budget announcement to freeze both the income tax personal allowance and the higher-rate threshold (and UEL) was forecast to raise £8.2 billion in 2025–26 (the final year of the then planned four-year freeze). But that estimate was predicated on a forecast for a much lower rate of inflation. The March 2023 Budget contained an updated number, suggesting that the four-year freeze to the income tax personal allowance and higher-rate threshold was now forecast to raise £23.4 billion in 2025–26, almost three times the original estimate.

The above is just part of the report.

To read it all go HERE