From Merry Christmas To A Messy New Year - What 2024 Has In Store

30th December 2023

2024 is going to be messy, for our living standards not just politics. The past two years have been dominated by rising energy and food bills, with everyone affected. It will be very different in 2024. Inflation falling back faster than expected means many will benefit from rising real wages. But politicians tempted to claim happy days have arrived should be cautious - it won't feel like that for everyone.

Higher interest rates actually made households better off in 2023 - higher returns on savings outweighed higher mortgage bills, raising household incomes by £19 billion. But the reverse will be true in 2024, as 1.5 million mortgagors see their annual bills rise by an average of £1,800. Millions of renters will also face big hits when it comes to housing costs - only outright owners will see strong living standards growth.

A New Year resolution to cut taxes (National Insurance cuts arrive on 6 January) won't last, with April's tax threshold rises cancelled - the net effect will be a tax cut for the top half of earners, and tax rises (or no change) for the bottom half. Overall, the richest half of Britain is likely to see incomes rise in the next financial year, but poorer households will see income falls, as targeted cost of living support comes to an end.

This mixed picture will present challenges for politicians trying to paint in primary colours in a critical election year. But the living standards story for the parliament as a whole is far simpler: British households will, for the first time on record, be poorer at the end of a parliament than at its start.

A messy 2024 lies ahead of us - not just politically, but for our living standards

The big macro story of 2023 was inflation rising far higher than forecast (the Bank of England has a review into that) before falling faster than expected (no new review has been announced yet...). The economic data year ended on a high note, with CPI inflation falling to 3.9 per cent in November, 0.7 percentage points lower than the Bank expected just last month. After a terrible two years for price rises, the journey from double digit to sub-four per cent inflation in just eight months was a Christmas present well worth having.

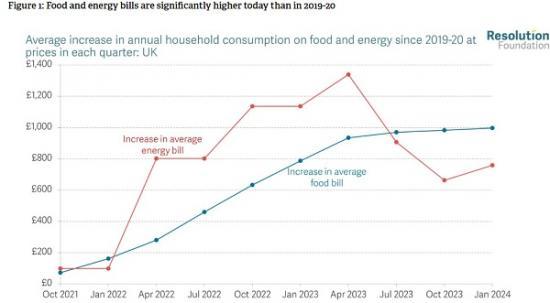

Britain's inflation journey, and the cost of living crisis to date, in part reflects fast-rising energy, and then food, prices. As we enter 2024, the average annual food bill will remain £1,000, and the average energy bill £760, higher than they were pre-pandemic, as Figure 1 shows. Everyone has to heat their home and put food on the table, so the core of the cost of living crisis has affected us all - though poorer households, who spend a greater share of their budgets on essentials, have been hit hardest.

Supporting recent inflation falls are the fact that food prices are no longer rising – and energy bills have fallen (and could fall another 14 per cent in April). Different forces instead are moving centre-stage in driving living standard developments. The shared nature of the crisis will evolve into a far more variable one in 2024, with a complex mix of winners and losers for politicians to communicate with in an election year.

Pay packets are growing again

Let's start with the biggest chunk of income. Nominal pay growth is now slowing, but inflation has been falling faster. So real pay growth has returned: the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) expects real earnings to grow by just shy of 1 per cent over 2024. This is welcome progress, even if it would still mean workers going into a late 2024 election with real wages lower than they were in 2006 (see Figure 2). Low earners will see bigger pay rises again. The National Living Wage will rise by 9.8 per cent in April – with increases up to 21 per cent in the minimum wage youth rates.

So, does the return of real wage growth mean a universal return to rising incomes as inflation falls back? Not so fast. The outlook for living standards – like life – is more complicated.

The impact of interest rates is interesting

Here comes the techy bit, concentrate. Interest rates are up a lot, with August's rise to 5.25 per cent looking to have capped the biggest rate-rising cycle in more than three decades. But financial markets have rate cuts of 1.34 percentage points pencilled in by the end of 2024. If rate rises are behind us and cuts are ahead, you’d be forgiven for thinking this means a boost to income growth next year. Forgiven, but probably wrong.

What has largely been missed is that rising interest rates have actually boosted household disposable incomes in 2023. Why? Because British households don’t have as much debt as they used to, and higher incomes for savers have arrived quicker than higher costs for borrowers (thanks to fixed-rate mortgages). For British households as a whole, annualised real income from savings interest is actually up £35 billion since the Bank of England started raising rates, more than twice the £16 billion increase in debt interest costs. This £19 billion net interest income boost amounts to 1 per cent of households’ disposable income. This is not normal (or remotely equally shared); in fact, it’s unprecedented in the recent history of UK rate-rising cycles, as shown in Figure 3.

Read the full by article by Torten Bell of the Resolution Foundation HERE