Changing Mortgage Preferences And Pandemic Saving Have Helped Uk Households Gain An Unprecedented Income Windfall From Rising Interest Rates

6th January 2024

Changes to the UK mortgage market and improving household balance sheets, including ‘forced saving' during the pandemic, have helped to deliver an unprecedented £16 billion household income boost from higher interest rates, according to new research published on Friday 5 January 2024 by the Resolution Foundation.

The latest Macroeconomic Policy Outlook examines the impact of the Bank of England's recent rate-rising cycle between December 2021 and August 2023, when interest rates increased from 0.1 to 5.25 per cent, on household balance sheets and incomes.

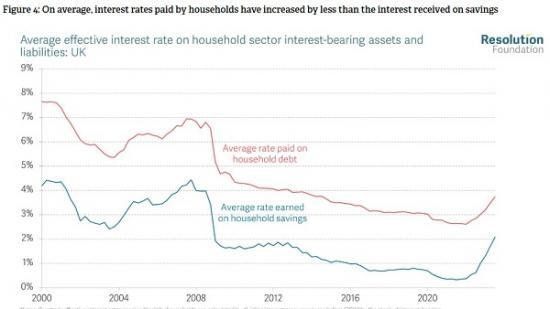

The Foundation notes that rate-rising cycles have tended to push up households' debt repayments by more than any extra income from savings during the past four cycles in the 1980s, 1990s and 2000s, thus directly reducing household incomes.

However, the opposite has happened over the course of the Bank's latest rate-rising cycle, delivering British households an unprecedented income boom of around £16 billion. This accounts for three-fifths of all household income growth over this period.

This income boost is not only unprecedented in recent UK economic history, but internationally too. Similar rate-rising cycles have delivered only a very modest income boost in the Eurozone, and an income fall in the US.

Changing mortgage preferences have played a key role, with fixed-rate deals replacing variable rate deals, and five-year fixes replacing two-year fixes as the most popular mortgage product. This has slowed the pass-through from interest rate rises to mortgage costs, with nearly two-in-five (37 per cent) households that had a mortgage when the Bank started rising rates in 2021 yet to see their fixed-rate deal come to an end.

In contrast, the income boost from higher savings interest has been more immediate - with real income from savings rising by £34 billion - more than offsetting the £18 billion rise in debt interest costs to give a net interest income boom of £16 billion.

Improving household balance sheets have also left Britain better placed to benefit from rising interest rates.

Back in 2007, households' outstanding debts stood at 150 per cent of disposable income, with interest-bearing savings worth 42 percentage points less, at just 108 per cent. Had households gone into this latest rate-rising cycle with such a large gap between debt and savings, it would have meant a much smaller boost to incomes, even with rising savings rates outpacing the average rate on household debt.

Since then, tighter mortgage lending criteria in the wake of the financial crisis have helped to reduce household debt to 136 per cent of total income, while ‘forced saving' during the pandemic has helped savings rise to 132 per cent of total income. So, by the time the Bank of England started raising rates at the end of 2021, the household balance sheet gap had closed from 42 to just 6 percentage points.

This income boost has not been felt evenly across households though, with older households the biggest beneficiaries due to having far stronger balance sheets.

The average household headed by someone aged 65-74 has three times as much interest-bearing savings than a household headed by someone aged 35-44 (£57,000 vs. £20,000), and seven times less outstanding debt (£14,000 vs. £98,000).

Looking ahead, the Foundation warns that this income boost could be almost completely unwound by the end of 2024. That's because household debt costs will continue to rise - another 1.5 million mortgagors will see their annual bill rise by £1,800, on average, when their fixed-rate deals end this year - while falling savings rates will reduce households' savings income boost.

Ironically, this means that the Bank's decision to raise rates between 2021 and 2023 could cause a significant living standards tailwind in 2024, even while the Bank starts to cut interest rates.

Simon Pittaway, Senior Economist at the Resolution Foundation, said, "When interest rates rose in the 80s, 90s and 2000s, household incomes tended to fall directly, with interest payments on debt rising by more than extra income from savings. But changes to the UK mortgage market and enforced saving during the pandemic have meant that the Bank's latest rate-raising cycle has actually boosted household incomes by £16 billion.

"The impact of the unlikely income boost has been very uneven - older, asset-rich households have gained the most, while younger mortgagor households have been hit hard.

"And while rising rates have boosted incomes over the past two years, they are likely to reduce them in the year ahead - presenting a fresh living standards challenge in an election year."

The Foundation's New Year Outlook 2024 calculated the net interest income boost to be £19 billion. This has now been updated and revised down to £16 billion.

The uneven impact of rising rates across households is an important part of monetary policy transmission. Spending from households with outstanding debts tends to be more sensitive to rising rates than households with savings. Between 2014 and 2020, the Bank of England’s NMG survey asked households how they would respond to a sustained increase in their mortgage repayments and, separately, interest income from savings. Half of households (47 per cent) said they would cut back on spending after a rise in mortgage repayments. But less than one-in-ten (8 per cent) said they would spend more after an increase in savings income.

This distributional impact of higher rates - plus their wider effects on the exchange rate, businesses, asset values and households’ incentives to save – was crucial in putting the brakes on spending and economic activity in 2023. But, in stark contrast to Britain’s previous rate-rising cycles, the direct impact of higher rates on aggregate household income acted in the opposite direction, boosting incomes and helping the UK economy avoid an outright recession. 2024 will be messy, as expected cuts in Bank rate will boost spending, but be offset by rising mortgage payments for many as more fixed-rate deals expire, and falling savings rates remove a rare source of income growth for many households. All of this suggests the Bank of England’s job of steering the economy won’t get easier any time soon.

Read the full report HERE

Pdf 11 Pages