The UK Must Invest In Further And Higher Education

7th September 2024

Education has not been a prominent part of the election debates, and further education even less so. But as Sandra McNally, Guglielmo Ventura and Gill Wyness argue, economic growth depends on paying much more attention to education, especially for the half of pupils who do not go to university.

Last time the Labour party was on the cusp of entering government, the mantra of Tony Blair was "education, education, education". Although not such a prominent part of the election debates this time, the issue is still just as important for inclusive growth.

Unfortunately, the share of GDP allocated to education is lower now than it was in 1997/98 (4.4 per cent in 1997/98; 5.6 per cent in 2010/11 and 4.3 per cent now). This is despite an increase in education participation in the UK, as in many other countries.

Compared with other developed economies, the UK continues to have a relatively unequal education distribution. Studies show that the percentage of university graduates in the UK is above the OECD average and comparable to levels in many other developed countries.

But there are too many young people who do not manage to achieve upper secondary education (equivalent to A-Levels and other Level 3 qualifications). The number of British 18-year-olds in education is considerably smaller than in France and Germany.

Roughly a half of young people go to further education colleges after Year 11 (age 16) and these institutions have suffered from draconian funding cuts brought about through the reduction in the budget for adult education (by 50 per cent between 2010/11 to 2020/21) as well as the reduction in real funding for 16-18-year-olds over this time period.

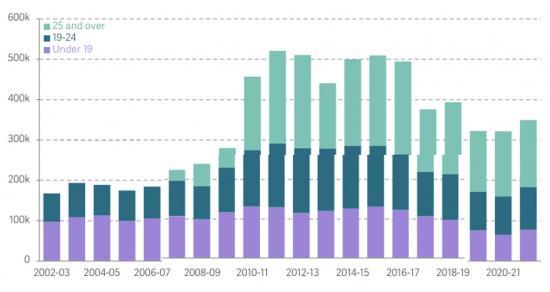

Aside from a higher quality of education for young people in further education colleges, there also needs to be more attention to the school-to-work transition, where young people have faced fewer opportunities over recent years. The number of apprenticeship starts has fallen sharply since 2016/17, especially for the under-25s.

In most countries (and in public discourse), apprenticeships are supposed to facilitate the school-to-work transition for young people, especially those who cannot or do not want to pursue the traditional higher education route, generating heftier economic returns in England than among older learners. There needs to be a clear way forward in which anyone who qualifies for the next higher level can expect to find a place of some kind. This would extend the ‘Robbins principle' (applied to higher education) to students who are not on an academic pathway. The Economy 2030 report discusses what an "apprentice guarantee" would look like and how it could be funded. It would be a revival of a similar plan legislated (but not implemented) by the Labour government in 2009. The plan would include ring-fencing a substantial part of the apprenticeship levy for younger people aged under 25.

Much as the next government needs to improve the quality of further education and expand apprenticeship opportunities for young people, it should avoid falling into the trap that this should be at the expense of people progressing to higher education. The much (mis)quoted article by Stansbury, Turner and Balls (2023) suggests a graduate premium that remains very high even outside London (albeit falling); it was 30 per cent in 2019 compared with 40 per cent in London.

If the UK economy is to grow, then it is especially important that "strategic sectors" (those in which the UK has a comparative advantage) are supported. These include financial and business services, the creative and cultural sector and life sciences. While these sectors are associated with a large pay premium throughout workers' careers across the whole skill distribution, they employ a much higher fraction of graduates than the rest of the economy. This suggests that to champion the growth of these strategic sectors, we need more graduates, not fewer.

The strategic sectors not only need more graduates but also more people with sub-degree qualifications at Levels 4 or 5 (for example Higher National Certificates; Higher National Diplomas). The problem is too many low-educated workers in the strategic sectors (not too many graduates).

Overall, there are much fewer people qualified by Levels 4/5 in the UK compared with countries such as Germany, Australia and Canada. This partly relates to how Level 4/5 qualifications have been funded. The introduction of the Lifetime Loan Entitlement (a tuition fee loan entitlement to the equivalent of four years of post-18 education) may create incentives for more institutions to provide these qualifications (and more individuals to take them up). But it seems unlikely that this will be enough on its own. David Willetts suggests pump-priming funding distributed according to priorities and a preference for collaboration of further and higher education as part of this.

Both further and higher education institutions need investment to provide the high-quality educational opportunities which are so badly needed. University finances were in relatively good shape following the major reforms of 2006 and 2012, with higher education funding beginning to recover after many years of decline. But those days are over.

The majority of universities' teaching resources come from tuition fees (with some coming from government grants). The annual tuition fee cap has only been allowed to increase once in the 12 years since 2012, when it rose from £9,000 per year to £9,250 per year. This, in conjunction with recent high inflation, means that the real value of tuition fees has fallen by around 20 per cent over the last decade, with overall per-student resources for teaching home students down 16 per cent since 2012.

The erosion of the fee cap has also encouraged universities to go after more lucrative foreign students, whose fees are unregulated. But recent declines in international student applications, linked to tougher visa restrictions (for example, rules that came into force in January mean that international students on taught courses can no longer bring family members to the UK) again threaten this source of university finance.

There are no easy answers but failure to invest in our further and higher education institutions is tantamount to failure to invest in a major source of economic growth: the education and skills of our young people and our future workforce.

This blog post is based on the Centre for Economic Performance's (CEP) election analysis: further and higher education.

The post represents the views of the author(s), not the position of LSE Business Review or the London School of Economics and Political Science.

Authors

Sandra McNally is professor of economics at the University of Surrey and director of the CEP's education and skills programme.

Guglielmo Ventura

Guglielmo Ventura is a research economist at LSE's Centre for Economic Performance (CEP).

Gill Wyness

Gill Wyness is professor of economics, and deputy director of the Centre for Education Policy and Equalising Opportunities (CEPEO) at the UCL Institute of Education, and an associate in CEP’s education and skills programme.

Note

This article is from, the London School of Economics blog

https://blogs.lse.ac.uk/businessreview/2024/07/03/the-uk-must-invest-in-further-and-higher-education/