Fiscal Rules And Investment In The Upcoming Budget

29th September 2024

The government is reportedly considering a change to the debt rule to allow for more borrowing for investment. The Institute for Fiscal Studies considers some of the options.

In her recent speech at the 2024 Labour Party conference, the new Chancellor Rachel Reeves promised that the fiscal event on 30 October will be a ‘Budget for investment'. She said that ‘growth is the challenge and investment is the solution' and declared that ‘it is time that the Treasury moved on from just counting the costs of investments, to recognising the benefits too'. This has fuelled widespread speculation about how a substantial top-up to investment plans might be reconciled with the new government's manifesto promise that ‘debt must be falling as a share of the economy by the fifth year of the forecast’.

One suggestion is that the government might adopt a looser debt target than the one adopted by the previous government, to allow for more borrowing for investment while staying within the letter of the fiscal rules.

In all of this, it is important to stress the distinction between the case for more investment and the case for more borrowing for investment. The government could, if it wished, offset any increase in investment through higher taxes, or through lower spending elsewhere (e.g. on public services or social security), and avoid the need for additional borrowing. That is, as Ms Reeves put it herself in her Mais Lecture, the government could ‘prioritise investment within a framework that would get debt falling as a share of GDP over the medium term’. It is perfectly coherent to think that the UK government should invest more, but that this should not be paid for through higher levels of borrowing.

Here, we put that debate to one side, and proceed on the assumption that the government does, for better or worse, wish to relax the fiscal rules to allow for more borrowing for investment. We consider some of the options available to the government, and the key issues and questions at hand in each case.

The key point is that there are advantages and disadvantages of each possible change (some, such as a target for public sector net worth, come with particularly large disadvantages) and no unambiguously ‘right’ answers. It is nonetheless hard to escape the suspicion that the government is attracted not by any theoretical advantages of a change in the debt rule, but by the fact that it would allow for significantly more borrowing for investment without any need for tough choices elsewhere. Rather than hide behind a technical change, if the government believes there is a principled case for more borrowing for investment, it should make it. This could be accompanied by a change in the debt rule to provide new, higher limits on borrowing and an indication of the government’s logic. Yet a large fiscal expansion would not be without risks, and impacts of debt and debt servicing costs cannot be disregarded entirely. Ensuring that the investment funded by that borrowing is - and is widely seen to be - spent well will be crucial.

What might it mean to recognise the benefits of investment?

It was not entirely clear what Ms Reeves meant when she said that ‘it is time that the Treasury moved on from just counting the costs of investments, to recognising the benefits too’.

One option would be to place a greater focus on the potential benefits of public investment in terms of the impact on the economy’s productive potential. A recent Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) paper set out in detail how the OBR plans to model the supply-side benefits of public investment going forward. Two key points are worth drawing out. First, the OBR’s estimated effects are not huge, and not large enough for investments to be self-financing for many years. Second, many of the supply-side benefits are expected to materialise only in the longer term, beyond the government’s current five-year forecast horizon. A permanent, sustained 1% of GDP increase in government investment is estimated to increase potential output by 0.4% after five years and by 2.4% after fifty years. The return to the exchequer would be smaller, given that the government would recoup less than half of this in additional tax revenues. In light of this, HM Treasury may wish to publish its own analysis on the potential benefits of investment projects, particularly where it considers that the returns are likely to be greater than those set out by the OBR for ‘average’ public investment, or where it is willing to take more of a ‘punt’ on certain kinds of investment.

In addition, the government may wish to consider a forecast horizon of longer than five years when thinking about the profile of debt, in order to allow for more of the benefits to materialise. One risk here is that a promise to have debt falling in (say) ten years’ time is even more susceptible to gaming (e.g. promises to raise taxes or cut spending only after the next election) than a promise to have debt falling in five years’ time. A longer forecast horizon might also make longer-term demographic- and climate-related fiscal pressures more explicit, and harder to ignore, meaning that a longer-term fiscal target is not automatically easier to meet.

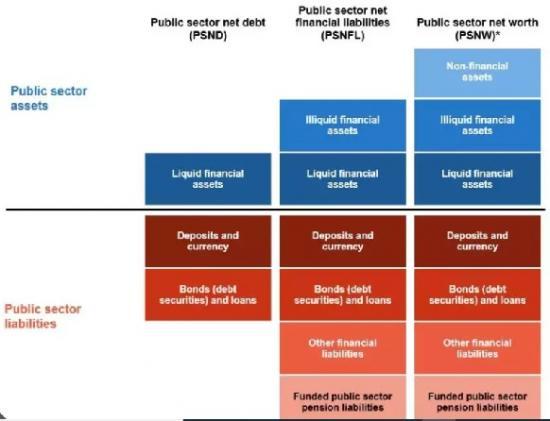

Another option would be to consider alternative measures of the government balance sheet that attempt to capture more of the government’s assets as well as its liabilities. This would reflect the ‘benefits’ of investment in that it would capture the assets created through that investment as well as the liabilities (debt) taken on to fund it. The next section considers some of these alternative measures.

Read the ful IFS report HERE