What Does Faster Take-up Of Electric Cars Mean For Tax Receipts? - Up To £30billion

15th December 2024

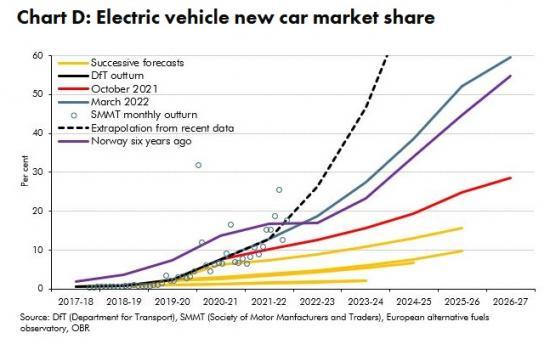

The largest single long-term fiscal cost of successful decarbonisation is the loss of revenue from motoring taxes as the vehicle stock moves from petrol and diesel engine vehicles to battery powered electric vehicles (EVs), which pay no fuel duty or vehicle excise duty (VED).a Efficiency gains in fossil-fuel vehicles and the shift to hybrids have already had modest effects on receipts. But the shift to fully electric vehicles now appears to be progressing more quickly than we had anticipated. In 2021, 11.6 per cent of cars sold were EVs compared to our October 2021 forecast of 9.5 per cent, as the share surged in the final months of the year. And the share of EVs in total car sales has repeatedly surprised us to the upside in recent years (Chart D).

It appears that take-up of EVs has moved onto a steeper part of the ‘S-curve' that many new technologies follow - with slow initial uptake while the technology is novel, followed by a rapid spread as it proves itself, before plateauing as take-up approaches saturation.b We have therefore revised up the assumed path of the EV market share significantly, basing it on the mid-point of the Society of Motor Manufacturers and Traders' (SMMT) ‘high' scenario and the Climate Change Committee's ‘tailwinds' scenario.c The share of EVs in new sales now reaches 59 per cent in 2026-27, up from 29 per cent in our October forecast.

This path would be similar to that witnessed in Norway over the past six years,d but even so implies some slowing relative to the very rapid rise in market share in the UK over the past two years (also Chart D). It is consistent with increasingly strong EV sales forecasts from several external bodies.

These updated EV assumptions have led us to revise down tax receipts by amounts that rise to £2.1 billion in 2026-27. Of this the £1.4 billion loss of fuel duty receipts represents a 4.4 per cent downward revision compared to our October forecast. The £0.6 billion loss of VED receipts is a proportionately larger 7.1 per cent downward revision.

That reflects the higher weight of vans and HGVs in fuel duty relative to VED (36 per cent versus 21 per cent in 2020-21). EVs can also obtain more generous capital allowances in the corporation tax system, in particular a 100 per cent first-year allowance until April 2025, rather than 6 to 18 per cent for petrol and diesel vehicles.

The higher EV share has therefore also reduced corporation tax receipts by £0.8 billion in 2024-25.

Charging infrastructure. The ability to charge EVs will influence the scope for further growth. Public charging points have been growing more slowly than the EV sales themselves, whereas charging points in private homes and workplaces have risen rapidly.g Since most drivers have access to off-street parking (72 per cent), we have assumed that charging infrastructure will not act as a major barrier to medium-term growth.h

Demand. EVs currently cost more to purchase than combustion engines but can have lower operating costs.i Consumer surveys point to strong demand for EVs.j

Supply. Global supply bottlenecks have hit the car industry recently, but manufacturers seemingly prioritised EVs over petrol and diesel vehicles in this period. Shortages of key inputs such as lithium for batteries would hinder the scaling up of EV production, whereas bottlenecks for other rare metals, such as palladium from Russia, could disproportionally hit combustion engine production.k The UK has already seen significant growth in the value of imported EVs (boosting customs duty receipts in the process).

Policies. There are many current and mooted policies that could affect the take-up of EVs. New sales of petrol and diesel cars will be banned from 2030 and hybrids from 2035. By 2024 the Government will introduce a new ‘zero emissions vehicles mandate'.l The Government could also implement its stated policy of raising fuel duty in line with RPI inflation (though that has not happened in more than a decade). And it has discussed expanding the Emissions Trading Scheme, which could cover road fuels,m as well as the need to tax motoring in different ways in the future.n It is difficult to know the extent to which consumers or manufacturers might respond to these potential policy changes if they are implemented - or how they might already be factoring expectations about them into their current purchase and production decisions.

It is, however, still the case that there is significant uncertainty around this assumption. Any of these factors could alter the path of the EV market share of new car sales. And the monthly data have been volatile of late, making it difficult to extract signal from noise. There are also uncertainties around the lifespan of vehicles and the decarbonisation of vans and HGVs that will determine the evolution of the broader motoring tax base.

Electric vehicles (EVs) currently enjoy free road tax (also called Vehicle Excise Duty). However, from 1 April 2025, drivers of electric cars in the UK will need to pay for road tax for the first time.

The new 2025 VED rules will impact hundreds of thousands of EV owners and their electric vehicle running costs. As well as paying for road tax for the first time, there will also be an expensive car tax supplement for electric cars with a list price that exceeds £40,000.

Many of the road tax changes will be backdated, which means drivers who have never paid for VED before will be required to do so after 1 April 2025.

To help you understand the 2025 electric vehicle road tax changes, we've put together this guide to set out what VED costs EV owners can expect right now - and how much they will pay when the tax rules change for electric car drivers in 2025.

How much do electric vehicle (EV) drivers pay for road tax?

At the moment, drivers of electric vehicles do not have to pay for road tax;. however, they must still get their vehicle taxed - even if they do not need to pay any money to do so.

To be exempt from paying VED, the electricity used to charge the vehicle must come from an external source, such as a private or public chargepoint; an electric storage battery not connected to any source of power when the vehicle is moving; or hydrogen fuel cells.

For almost all other vehicles – including hybrids which can generate their own electricity – you must pay vehicle tax every year.

How much will electric vehicle (EV) road tax be in 2025?

From 1 April 2025, drivers of electric vehicles will need to pay for VED – road tax. Announced by the Government in the 2022 Autumn Budget, Chancellor Jeremy Hunt stated: "To make our motoring tax system fairer I've decided that electric vehicles will no longer be exempt from Vehicle Excise Duty (VED)."

The 2025 EV road tax changes are as follows:

New zero-emission cars registered on or after 1 April 2025 will be liable to pay the lowest first-year rate of VED (which applies to vehicles with CO2 emissions 1 to 50g/km) currently £10 a year.

From the second year of registration onwards, they will move to the standard rate, currently £190 a year

Zero emission cars first registered between 1 April 2017 and 31 March 2025 will also pay the standard rate

The Expensive Car Supplement exemption for electric vehicles is due to end in 2025. New zero emission cars registered on or after 1 April 2025 will therefore be liable for the Expensive Car Supplement. The Expensive Car Supplement currently applies to cars with a list price exceeding £40,000 for five years and is currently £410 a year. This means EV drivers with an 'expensive car' will pay up to £600 a year for road tax

Zero and low emission cars first registered between 1 March 2001 and 30 March 2017 currently in Band A will move to the Band B rate, currently £20 a year

Zero-emission vans will move to the rate for petrol and diesel light goods vehicles, currently £335 a year for most vans

Zero-emission motorcycles and tricycles will move to the rate for the smallest engine size, currently £25 a year

Rates for Alternative Fuel Vehicles and hybrids will also be equalised