Was the Bounce Back Loan Scheme Successful, Even Considering Fraud?

12th September 2025

The COVID-19 pandemic presented governments worldwide with the unprecedented challenge of protecting both public health and national economies.

In the United Kingdom, one of the flagship interventions to support small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) was the Bounce Back Loan Scheme (BBLS), launched in May 2020.

Its design reflected an urgent policy priority: speed of delivery over financial due diligence. The scheme provided 100 per cent government-backed loans of up to £50,000 to eligible businesses, with minimal credit checks, aiming to keep firms afloat during prolonged lockdowns and demand shocks (NAO, 2020).

This essay examines whether the BBLS can be considered a success, even when its well-documented fraud problems are taken into account. It begins by considering the scheme’s objectives and achievements, before turning to evidence of fraud, abuse, and default. It then reviews criticisms from oversight bodies and concludes with an assessment of its legacy, weighing short-term effectiveness against long-term costs.

Objectives and Achievements

The primary objective of BBLS was to deliver finance rapidly to SMEs excluded from other forms of credit. According to official data, by June 2025 approximately £46.48 billion had been drawn under the scheme, distributed to over 1.5 million businesses (HM Government, 2025).

The accessibility of the scheme was unparalleled: applicants were required only to self-certify eligibility, and funds were often released within 24 to 48 hours (NAO, 2020).

By this measure, the scheme was highly successful. Surveys of business owners reported that loans enabled them to pay fixed costs, retain staff, and survive temporary closures (British Business Bank, 2021). Without such intervention, it is plausible that thousands of firms would have collapsed, with knock-on effects for employment and supply chains. In this sense, the scheme complemented other emergency measures, such as the Coronavirus Job Retention Scheme (CJRS), to preserve the productive capacity of the economy.

Fraud and Abuse

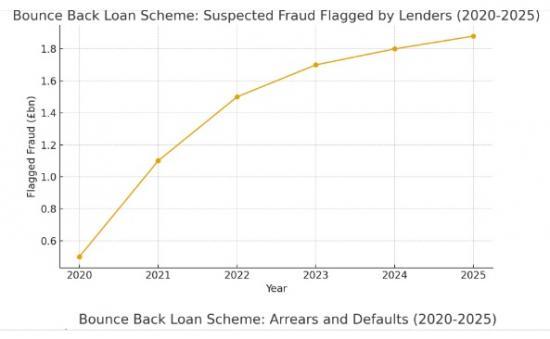

Despite its rapid impact, the scheme was plagued by fraud and abuse. The most recent government data show that by June 2025 lenders had flagged approximately £1.88 billion of loans as suspected fraud, around 4 per cent of total lending (HM Government, 2025).

Independent analyses, however, suggest that actual losses could be far higher. ROE Lawyers (2024) estimate that between £3 billion and £5 billion may ultimately be lost through fraudulent claims, equating to more than 10 per cent of the total scheme value.

Fraud took multiple forms. Some applicants invented fictitious businesses or inflated turnover figures to claim the maximum loan. Others used shell companies or newly incorporated entities to access funds. In more complex cases, organised crime groups exploited the scheme by applying for loans en masse using stolen identities (NAO, 2020). The structure of BBLS, with limited checks and full government guarantees, created what the National Audit Office described as a “very high risk of fraud” (NAO, 2020, p. 5).

Defaults and Financial Risk

Fraud was not the only threat to the taxpayer. Many legitimate borrowers have defaulted on their loans due to the prolonged economic disruption of the pandemic and the subsequent cost-of-living crisis. As of June 2025, 4.42 per cent of loans were in arrears and 0.79 per cent had defaulted but not yet been claimed under the government guarantee (HM Government, 2025). Given the scheme’s size, even modest default rates translate into billions of pounds of potential losses.

The long-term recovery outlook is uncertain. While some businesses may eventually repay, others have already entered insolvency. The Insolvency Service has reported a surge in disqualifications of company directors linked to BBLS abuse, with over 600 directors struck off between 2022 and 2023 alone (Business Rescue Expert, 2023).

Enforcement and Accountability

A further weakness of BBLS lies in enforcement. The National Investigation Service (NATIS), the body tasked with pursuing fraud cases, has been criticised for poor performance. By 2025, despite costing the taxpayer £38.5 million, NATIS had secured only 14 convictions (Construction News, 2025). Responsibility for fraud investigations has since been transferred to the Insolvency Service, which has had greater success in securing civil sanctions such as director disqualifications but has still delivered relatively few criminal prosecutions (Insolvency Service, 2024).

The failure to deliver meaningful enforcement outcomes has attracted criticism from Parliament. The Public Accounts Committee (2022) concluded that the scheme was rolled out with “unacceptable risks to taxpayers” and that the government had been slow to act against fraud. The Committee also warned that weak recoveries risked undermining public confidence in emergency support schemes.

Policy Trade-Offs: Speed versus Oversight

The shortcomings of BBLS highlight a classic policy trade-off. During a crisis, the imperative is to act quickly to prevent economic collapse. This explains why the government chose to prioritise rapid disbursement of funds over due diligence. In the short term, the strategy worked: businesses received lifelines at record speed. Yet in the long term, the costs of inadequate oversight became clear.

The National Audit Office (2021) observed that while the scheme helped avoid immediate mass insolvency, its design left the government “exposed to large losses from fraud and defaults.” In hindsight, alternative models could have balanced speed and accountability more effectively, such as phased lending with initial emergency grants followed by stricter loan assessments.

Wider Economic and Political Implications

The legacy of BBLS extends beyond financial losses. Public discourse around “Covid loan fraud” has eroded trust in government financial management. Media reports of individuals securing loans for luxury spending or fictitious firms have reinforced perceptions of waste and mismanagement (The Guardian, 2023). Politically, the scheme has become a focal point for criticism of pandemic spending more broadly.

On the other hand, defenders of the scheme argue that the scale of fraud should be seen in context. At around £1.9 billion officially flagged, fraud represents roughly 4 per cent of total lending—significant, but not catastrophic in light of the extraordinary circumstances (HM Government, 2025). Moreover, the counterfactual scenario of mass SME failure may have produced far greater economic and fiscal costs through unemployment, welfare spending, and lost tax revenues.

Conclusion

The Bounce Back Loan Scheme was both a triumph and a failure. It was a triumph in achieving its immediate aim: keeping small businesses alive during an economic emergency. It was a failure in terms of oversight, leaving taxpayers with billions in potential losses through fraud and default, and exposing weaknesses in the UK’s enforcement capacity.

On balance, the scheme should be considered a short-term success but a long-term liability. It demonstrated the benefits of decisive government action in a crisis, but also the dangers of sacrificing accountability for speed. The central lesson is that emergency policy design must incorporate at least minimal safeguards to protect public funds without undermining urgency. As future crises are inevitable, this balance between speed and control will remain a critical challenge for policymakers.

References

Business Rescue Expert (2023) Over half of UK disqualified company directors were struck off for Bounce Back Loan fraud. [online] Available at: https://www.businessrescueexpert.co.uk/over-half-of-uk-disqualified-company-directors-were-struck-off-for-bounce-back-loan-fraud/

[Accessed 12 Sept. 2025].

Construction News (2025) Insolvency Service to take over Covid loan fraud investigations. [online] Available at: https://www.constructionnews.co.uk/financial/insolvency-service-to-take-over-covid-loan-fraud-investigations-15-05-2025/

[Accessed 12 Sept. 2025].

HM Government (2025) COVID-19 loan guarantee schemes: repayment data, June 2025. [online] Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/covid-19-loan-guarantee-schemes-repayment-data-june-2025/covid-19-loan-guarantee-schemes-repayment-data-june-2025

[Accessed 12 Sept. 2025].

Insolvency Service (2024) Annual report and accounts 2023 to 2024. London: HM Stationery Office.

National Audit Office (2020) Investigation into the Bounce Back Loan Scheme. London: NAO.

National Audit Office (2021) Initial learning from the government’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic. London: NAO.

Public Accounts Committee (2022) The Government’s business support schemes in response to COVID-19. London: House of Commons.

ROE Lawyers (2024) Bounce Back Loan fraud and rogue directors. [online] Available at: https://roelawyers.com/london-law-firm/insights/bounce-back-loan-fraud-2024-11-19.aspx

[Accessed 12 Sept. 2025].

The Guardian (2023) UK taxpayers left footing bill as number of fraudulent Covid loans soars. [online] Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/business/2023/sep/14/uk-taxpayers-left-footing-bill-as-number-of-fraudulent-covid-loans-soars

[Accessed 12 Sept. 2025].

Latest fraud example published on 11 September 2025

London Covid fraudster jailed after using fraudulently obtained Bounce Back Loans to fund trading in Ghana

Jail term for Bounce Back Loan fraudster who exploited government scheme.

Eric Agyeman fraudulently secured £130,000 across three Bounce Back Loan applications in 2020 by fabricating turnover figures for a company which never traded

Agyeman transferred more than £40,000 of the funds into a separate trading operation purchasing goods for export to Ghana through an associate who would sell them and return commission payments

The 46-year-old was jailed and banned as a company director after pleading guilty to fraud and money laundering following investigations by the Insolvency Service

A London fraudster has been jailed after illegally securing three Bounce Back Loans and using the funds to buy and ship goods to Ghana for resale.

Eric Agyeman obtained £130,000 in three Bounce Back Loans for DOK Logistics UK Ltd when businesses were only entitled to a single loan under the scheme.

Agyeman invented turnover figures of as much as £375,000 when the company never actually traded.

The 46-year-old then used more than £40,000 of the Bounce Back Loans to fund a separate business scheme in Ghana, where he would send goods from the UK to an associate in the West African country and receive commission on the sales.

Agyeman, of Mace Street, London, was sentenced to two years and two months in prison at the Old Bailey on Tuesday 9 September after pleading guilty to offences of fraud and money laundering.

He was also disqualified as a company director for five years.

David Snasdell, Chief Investigator at the Insolvency Service, said:

Eric Agyeman brazenly exploited a scheme designed to help struggling companies during the pandemic for his own personal gain, using the funds for a business operation in Africa.

Agyeman’s admission that he simply ‘made up’ turnover figures shows a complete disregard for the taxpayer-funded support that was meant to keep legitimate businesses afloat during the most challenging period in recent economic history.

It may now be more than five years since the start of the pandemic, but the Insolvency Service remains committed to pursuing fraudsters who obtained Covid support funds they were not entitled to and ensuring that justice is served.

DOK Logistics UK Ltd was set up on Companies House in February 2020, with its nature of business described as “other transportation support activities”.

However, Insolvency Service investigations revealed that the company was not trading at the beginning of March 2020, as was required to qualify for Covid support funds.

Indeed, there is no evidence that the company ever traded.

Agyeman first applied for a Bounce Back Loan of £30,000 in early May 2020, on the first day the scheme opened.

In the application, he falsely claimed that DOK Logistics UK Ltd’s estimated turnover was £120,000.

Just nine days later, he applied to a different bank for a £50,000 Bounce Back Loan, this time stating that the company’s estimated turnover was £275,000.

Agyeman’s third fraudulent application came in July 2020, when he provided an estimated turnover of £375,000 to secure another £50,000 Bounce Back Loan.

In interviews with the Insolvency Service, he acknowledged the turnover figures were made up, admitting he “took it for granted” and “didn’t really put much emphasis into thinking about the figures” and that “it’s just something I just made up.”

Even if Agyeman’s estimated turnover figures were accurate, businesses were only entitled to a single loan under the terms of the scheme.

A total of £44,415 of the fraudulently obtained funds was channelled into buying goods that were then transported to his contact in Ghana for onward sale, generating commission payments back to Agyeman.

The money from goods sold in Ghana would be converted to British pounds locally, and visitors to the UK would physically bring this cash back to him.

Insolvency Service investigators also concluded that other unexplained payments were not for the economic benefit of DOK Logistics UK Ltd.

The Insolvency Service is seeking to recover the fraudulently obtained funds under the Proceeds of Crime Act 2002.