Unfair dismissal - Day One Rights

27th October 2025

The Government should keep but reduce ‘qualifying periods' for unfair dismissal protection says a Resolution Foundation report published on 26 October 2025.

The Government's Employment Rights Bill is important and welcome.

The Government's Employment Rights Bill (ERB) is nearing the end of its parliamentary journey. It's a sprawling, 300-page piece of legislation containing a lot of measures (27 by one count), covering big areas like collective bargaining in social care, union law, rights for shift workers, and sick pay, as well as some narrower changes like the allocation of tips.

One aim of the Bill is to reduce job-related insecurity. For many (generally low-paid) British workers, insecurity is too high, and it's been a long time since policy makers tried to do anything about this. For example, there are 1.2 million workers on zero-hours contracts, and there is currently nothing in UK law to stop employers cancelling those workers' shifts without notice. When this happens it creates hassle and anxiety, and leads to unpredictable pay and income. The Bill will make employers compensate workers when their shifts are cancelled without proper notice and will give workers a right to a contract with guaranteed hours.

Of course, reducing workers' insecurity is a good thing to do, but there are trade-offs. To take an extreme example, we could end job-related insecurity entirely by banning employers from making dismissals or from making any changes to shift patterns. This would definitely make workers feel more secure, and there might be other benefits too: employers might invest more in training their current staff. But there would also be problems. Employers would be nervous about hiring new workers or offering shifts, and this would make life harder for job seekers, and could harm the economy if it slowed the movement of workers to jobs where they can be most productive. So, the question is how to get the balance right.

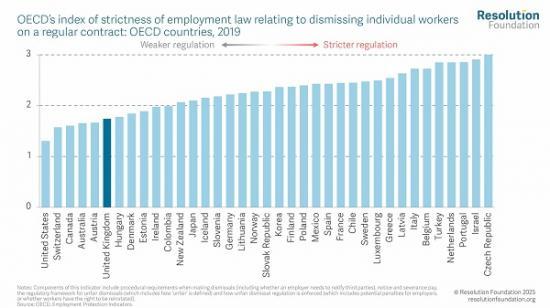

The UK's employment law starts from a fairly extreme position compared to other rich countries. We do little to protect workers financially when they can't work (unemployment benefits and sick pay are low), and there are few constraints on employers when it comes to making dismissals (there are only five OECD countries where it is easier to fire someone) or using flexible forms of work. OECD’s scores for the overall strength of employment law relating to dismissing workers is shown in Figure 1. We are also less good at enforcing our labour market laws; last week saw another round of naming and shaming of employers failing to pay the minimum wage, but more impactful would be higher fines. This low-protection/low-regulation starting position means the reforms in the ERB will mainly make the UK less of an international outlier, rather than moving us to the other end of the scale.

... but it should change tack on unfair dismissal

One exception to this picture of the ERB as bringing the UK more into line with other countries is the plan to make protection from unfair dismissal a ‘day one’ right. That will take the UK from one end of the international scale to the other - see Figure 2 below.

Reform here is definitely needed. Currently, protection from unfair dismissal kicks in only when someone has been in the job for two years. That doesn’t mean employers can do what they like within those two years: if they make a dismissal which is discriminatory, or dismiss someone because they’re a whistleblower, for example, then they could be taken to an employment tribunal. But in general, in the first two years, employers don’t need to demonstrate that dismissals are ‘fair’ (which would require that they are happening for a fair reason (including redundancy and performance) and happening through a fair process). As it stands, the law places no fairness constraint on dismissing workers who may be well-established in their jobs, albeit for less than two years.

Figure 2 Making unfair dismissal a ‘day one’ right would be a big change from the UK’s current two-year qualifying period

Read the full report HERE