I grew up in the world's coldest city without central heating. Here's what the world can learn from us - China - 下面是文章的简体中文翻译(保留了原有结构和小标题风格)

31st December 2025

On winter mornings in Harbin, where the air outside could freeze your eyelashes, I would wake up on a bed of warm earth.

Harbin, where I grew up, is in northeast China. Winter temperatures regularly dip to -30°C and in January even the warmest days rarely go above -10°C. With about 6 million residents today, Harbin is easily the largest city in the world to experience such consistent cold.

Keeping warm in such temperatures is something I've thought about all my life. Long before electric air conditioning and district heating, people in the region survived harsh winters using methods entirely different from the radiators and gas boilers that dominate European homes today.

Now, as a researcher in architecture and construction at a British university, I'm struck by how much we can learn from those traditional systems in the UK. Energy bills are still too high, and millions are struggling to heat their homes, while climate change is expected to make winters more volatile. We need efficient, low-energy ways to stay warm that don't rely on heating an entire home with fossil fuels.

Some of the answers may lie in the methods I grew up with.

A warm bed made of earth

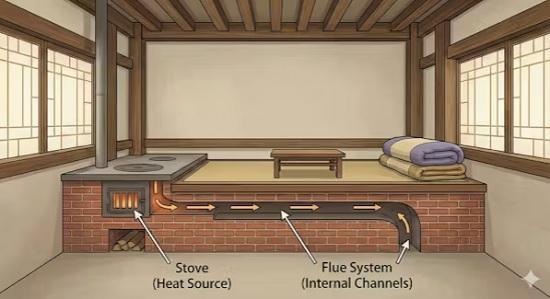

My earliest memories of winter involve waking up on a "kang" - a heated platform-bed made of earth bricks that has been used in northern China for at least 2,000 years. The kang is less a piece of furniture and more a part of the building itself: a thick, raised slab connected to the family stove in the kitchen. When the stove is lit for cooking, hot air travels through passages running beneath the kang, warming its entire mass.

To a child, the kang felt magical: a warm, radiant surface that stayed hot all night long. But as an adult - and now an academic expert - I can appreciate what a remarkably efficient piece of engineering it is.

Unlike central heating, which works by warming the air in every room, only the kang (that is, the bed surface) is heated. The room itself may be cold, but people warm themselves by laying or sitting on the platform with thick blankets. Once warmed, its hundreds of kilograms of compacted earth slowly release heat over many hours. There are no radiators, no need for any pumps, and no unnecessary heating of empty rooms. And since much of the initial heat was generated by fires we'd need for cooking anyway, we saved on fuel.

Maintaining the kang was a family undertaking. My father - a secondary school Chinese literature teacher, not an engineer - became an expert at constructing the kang. Carefully building layers of coal around the fire to keep it alive over the night would be my mum's job. Looking back, I realise how much skill and labour was involved, and how much trust families placed in a system that required good ventilation to avoid carbon monoxide risks.

But for all its drawbacks, the kang delivered something modern heating systems still struggle to deliver: long-lasting warmth with very little fuel.

Similar approaches across East Asia

Across East Asia, approaches to keeping warm in cold weather evolved around similar principles: keep heat close to the body, and heat only the spaces that matter.

In Korea, the ancient ondol system also channels warm air beneath thick floors, turning the entire floor into a heated surface. Japan developed the kotatsu, a low table covered by a heavy blanket with a small heater underneath to keep your legs warm. They can be a bit costly, but they're one of the most popular items in Japanese homes.

Clothing was also very important. Each winter my mum would make me a brand new thick padded coat, stuffing it with newly fluffed cotton. It's one of my loveliest memories.

Europe had similar ideas - then forgot them

Europe once had similar approaches to heating. Ancient Romans heated buildings using hypocausts, for instance, which circulated hot air under floors. Medieval households hung heavy tapestries on walls to reduce drafts, and many cultures used soft cushions, heated rugs or enclosed sleeping areas to conserve warmth.

The spread of modern central heating in the 20th century replaced these approaches with a more energy-intensive pattern: heating entire buildings to a uniform temperature, even when only one person is home. When energy was cheap, this model worked, even despite most European homes (especially those in the UK) being poorly insulated by global standards.

But now that energy is expensive again, tens of millions of Europeans are unable to keep their homes adequately warm. New technologies like heat pumps and renewable energy will help - but they work best when the buildings they heat are already efficient, allowing for lower set point for heating, and higher set points for cooling.

This highlights why traditional approaches to warming homes still have something to teach us. The kang and similar systems show that comfort doesn't always come from consuming more energy - but from designing warmth more intelligently.

Author

Yangang Xing

Associate Professor, School of Architecture Design and the Built Environment, Nottingham Trent University

PHOTO

A traditional Chinese kang bed-stove. Google Gemini,

CC BY-SA

Note

This article is from The Conversation web site. To read it with links to more information, photos etc go HERE

在哈尔滨的冬日清晨,外面的寒气足以冻住你的睫毛,而我却会在一张由温暖泥土构成的床上醒来。

我在哈尔滨长大,这座城市位于中国东北。冬季气温经常跌到零下30℃,而在一月份,即使是最暖和的日子也很少高于零下10℃。如今这里约有600万居民,是世界上经历如此严寒气候的最大城市。

如何在这样的温度中保持温暖,是我一生都在思考的问题。在电力空调和集中供暖出现之前,这片地区的人们用与今天欧洲家庭普遍使用的暖气片和燃气锅炉截然不同的方式来度过严冬。

如今,作为一名在英国大学从事建筑与施工研究的学者,我愈发意识到,我们在英国可以从这些传统系统中学到很多。能源账单依然过高,数百万人在为给家里供暖而挣扎,而气候变化预计会让冬天更为极端。我们需要高效、低能耗的保暖方式,而不是依赖化石燃料来加热整栋房子。

答案或许就藏在我成长时接触的那些方法里。

一张由泥土制成的温暖床铺

我最早的冬天记忆,是在"炕"上醒来——一种由泥土砖砌成的加热平台式床铺,在中国北方已经使用了至少两千年。炕不仅仅是一件家具,几乎是房屋结构的一部分:一块与厨房炉灶相连的厚重抬高土台。做饭时点燃炉灶,热空气就会沿着炕底下的通道流动,加热整个平台。

对孩子来说,炕简直像魔法一样:一个整夜都温暖的辐射面。而作为成年后的我——如今还是一名学者——我能更深刻地体会到它是多么高效的工程。

与通过加热整间屋子的中央供暖不同,炕只加热身体直接接触的床面。房间本身也许很冷,但人们只需躺或坐在炕上,盖上厚厚的被褥就能保暖。被加热后的数百公斤夯土会在数小时内缓慢释放热量。不需要暖气片、不需要水泵,也不会浪费能源去加热空房间。而且,由于最初的热量大多来自做饭时本就要生的火,我们大大节省了燃料。

维护炕是一个家庭共同承担的任务。我的父亲——一位中学语文老师,而非工程师——却成了砌炕的专家。为了让火在夜里持续燃烧,我母亲会小心地在火周围堆上煤炭。回想起来,我意识到其中蕴含了多少技巧和劳动,以及家庭对这一系统的信任,因为它必须有良好通风以避免一氧化碳风险。

尽管存在不足,炕带来了现代供暖系统仍难以实现的效果:用极少的燃料维持持久的温暖。

东亚地区的相似方式

整个东亚在寒冷天气中取暖的思路都相似:将热量留在人体附近,并只加热真正需要的空间。

在韩国,古老的"温突"(ondol)系统也会让热空气在厚实的地板下流动,使整个地面变成加热面。日本则发展出了“被炉”(kotatsu),一种盖着厚被子的矮桌,下面放置小型取暖器来温暖双腿。虽然有点花费,但它是日本家庭最受欢迎的物件之一。

衣物也很重要。每年冬天,我母亲都会给我做一件新的厚棉袄,用新弹的棉花填充——这是我最温馨的记忆之一。

欧洲也有类似传统——但后来遗忘了

欧洲过去也曾有类似的供暖方式。例如古罗马的“地炕”(hypocaust)通过让热空气在地板下循环来加热建筑。中世纪家庭在墙上挂厚重的挂毯以减少穿堂风,许多文化还使用柔软坐垫、暖地毯或封闭式床铺空间来保持温暖。

但20世纪现代中央供暖的普及取代了这些方法,转而形成一种高能耗模式:即使家中只有一个人,也要把整栋建筑加热到统一温度。在能源便宜的年代,这一模式还能运作,尽管欧洲许多房屋(尤其是英国)在全球标准中属于隔热性能较差的建筑。

如今能源再次变得昂贵,数千万欧洲人无法让家中保持足够温暖。热泵和可再生能源等新技术会有所帮助——但它们在建筑本身高效的情况下才能发挥最佳效果,从而实现更低的供暖设定、更高的制冷效率。

这也凸显了传统供暖方式的重要启示。炕等系统提醒我们:舒适并不总是意味着消耗更多能源,而在于更聪明地设计供暖方式。

作者

杨刚行

英国诺丁汉特伦特大学

建筑设计与建筑环境学院副教授

照片

传统的中国炕炉床。Google Gemini

CC BY-SA 4.0

注释

本文来自 The Conversation 网站。阅读包含更多信息和图片的原文请点击:

如果你还想要润色、简化、变成更口语化版本或用于课堂教学,我也可以继续协助。

需要我把它变成 PDF、带拼音、或做摘要吗?