Are School Transport Costs Breaking Council Budgets

18th January 2026

Why councils across England and Scotland are still losing control of school transport costs and why fixing it is harder than it looks

For years, school transport was a quiet, technical line in council budgets were important, but manageable. That era is over. Across England and Scotland, home-to-school transport has become one of the fastest-growing, hardest-to-control pressures on local government finances. Councils are now spending hundreds of millions of pounds more each year than they did a decade ago, and many say the system is no longer financially sustainable.

Yet despite tightening rules, consulting the public, and stripping out discretionary generosity, costs keep rising. The reason is uncomfortable but unavoidable school transport has become the point where education law, housing policy, geography, disability rights and austerity collide and councils are trapped in the middle.

A problem years in the making

In both England and Scotland, councils have long had a statutory duty to ensure children can reasonably access education. This includes providing free transport where pupils live beyond set walking distances (typically 2 miles for younger children, 3 miles for older pupils) or where walking is unsafe or unreasonable.

For decades, many councils went further than the law strictly required. Policies were expanded, distances shortened, discretionary support added. These decisions were often well-intentioned and designed to promote inclusion, parental choice, rural sustainability or access to specialist provision. But cumulatively, they embedded an assumption that transport would always be provided, whatever the distance or complexity.

At the same time, wider structural changes were under way:

Rising numbers of pupils with SEND / ASN, often requiring bespoke transport

School closures and consolidations, particularly in rural areas

Housing pressures pushing families further from schools

Increased reliance on taxis and private contracts, often at premium cost

Labour shortages driving up driver and operator prices

The result has been a slow-burn financial crisis that is now fully visible.

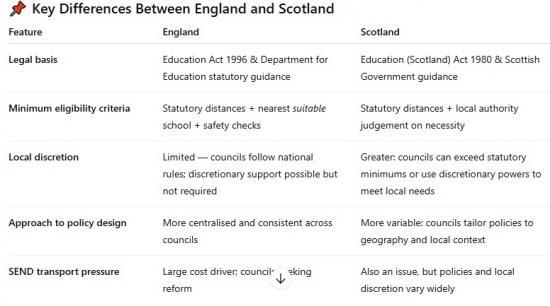

England: tightly regulated, rapidly escalating

In England, school transport is governed by a highly prescriptive national framework under the Education Act 1996 and Department for Education guidance. Councils must provide free transport where statutory criteria are met, particularly where a child attends their nearest suitable school and lives beyond walking distance.

This system offers consistency — but little flexibility.

English councils now spend well over £2 billion a year on home-to-school transport, with SEND transport the dominant cost driver. Many pupils travel long distances to specialist schools, often alone, with escorts, in taxis commissioned at short notice and renewed annually. Once a need is established, councils have very limited scope to withdraw or downgrade support.

As budgets have tightened, councils have responded by:

Aligning policies strictly with statutory minimums

Removing discretionary transport beyond legal duties

Introducing or increasing parental contributions (especially post-16)

Enforcing "nearest suitable school" rules more rigorously

Promoting independent travel training and public transport use

These measures save money at the margins — but they do not touch the underlying drivers of demand. Nor can councils legally take into account whether a family "chose" to live far away. In practice, English councils are left managing demand they cannot meaningfully influence.

Scotland: more discretion, the same pressure

Scotland operates under a different legal culture. The Education (Scotland) Act 1980 gives councils a duty to provide transport they "consider necessary", supported by national guidance rather than rigid statutory tests. This gives Scottish councils greater discretion and results in far more variation between authorities.

Some councils historically offered generous transport entitlements, particularly in rural areas. Others set policies closer to statutory minimums. But despite this flexibility, Scottish transport costs have also surged, with total spend approaching £100 million a year and rising fast.

Large rural and island councils face unique pressures:

Long distances between settlements

Sparse or non-existent public transport

Limited local school choice

Heavy reliance on private operators

Higher per-pupil costs

In response, Scottish councils have begun to:

Tighten qualifying distances to statutory norms

Review eligibility more aggressively

Shift from private taxis to in-house fleets

Encourage use of free bus passes

Centralise decision-making through transport panels

Yet even here, councils face limits. ASN transport remains strongly protected. Geography cannot be legislated away. And local political resistance is fierce when transport changes are seen as undermining rural viability.

The uncomfortable question: did policy remove the incentive to live near schools?

A growing number of councillors now ask a question once considered taboo - has the system itself encouraged unsustainable behaviour?

Over many years, transport policies have quietly weakened the link between where families live and how children get to school. When transport is guaranteed beyond a certain distance, the cost of travel is socialised not borne by the household making the location decision.

In theory, this creates a moral hazard. In practice, the picture is more complex.

Many families do not freely "choose" to live far from school:

Housing near schools is often unaffordable

Social housing allocations prioritise availability, not proximity

Specialist provision may be far away by necessity

Rural communities may have no alternative

Moreover, the law does not permit councils to retrospectively penalise families for housing decisions. Education access is a child's right, not a consumer transaction.

As a result, councils are forced to act indirectly — tightening eligibility, enforcing "nearest suitable school" rules, and gradually resetting expectations. This is not about punishment, but about re-establishing a connection between planning, schooling and transport that has eroded over time.

Why this problem won't go away

Despite consultations, policy rewrites and political debate, school transport remains a structural problem, not a managerial one.

Councils are caught between:

Legal duties they cannot escape

Social expectations they did not create alone

Housing systems they do not control

Education systems that increasingly specialise and centralise

Budget constraints that grow tighter each year

England's tightly regulated model limits reform without national legislative change. Scotland's discretionary model allows local tailoring but not immunity from geography or demand.

In both systems, the same truth applies. You cannot fix school transport costs without addressing how schools are planned, where families live, and how additional needs are met.

The school bus as a warning light

School transport is no longer a niche service. It is a warning light on the dashboard of local government, signalling deeper failures of coordination between policy areas that are treated as separate but operate as one.

Councils are doing what they can — tightening rules, removing generosity, and asking difficult questions. But without long-term alignment between education provision, housing policy and transport planning, they will continue to firefight rather than solve.

The school run did not break council budgets overnight. It did so slowly, quietly, and legally until the bill finally arrived.

The Highland Council

most up-to-date picture of how much Highland Council spends on school transport in recent years — based on published budget figures and local reporting:

Annual Transport Budget

According to Highland Council's own transport strategy documents, the annual budget for home-to-school transport is about £11.43 million. This covers the council’s ongoing statutory transport costs for school pupils.

Overall School Transport Costs

Local news reporting from January 2025 indicates Highland Council has been spending around £25 million a year on school transport services, including contracted bus and coach services. In that context, the council was preparing to acquire a local coach operator (D&E Coaches) for roughly £5.5 m-£6 m with the explicit aim of managing those costs more efficiently.

Why There’s a Spending Discrepancy

The difference between the £11 m annual budget line and the £25 m annual spending figure comes down to what’s being counted:

The official budget number reflects the council’s core statutory transport programme (home-to-school routes it directly funds).

The larger figure reported locally includes all contracts, taxes, private hires and subsidised routes that Highland runs or commissions a broader measure of transport costs.

This mirrors a pattern seen across Scottish councils, where the cost of pupil transport — especially for students with additional support needs (ASN) has grown substantially in recent years and now accounts for a large share of taxi and bus spending.

Moves to Control Costs

Highland Council has been taking steps to reduce these high costs, including:

Launching an in-house bus service pilot, which carried both pupils and members of the public and delivered savings on some routes (e.g., saving £173,000 annually on a Strathdearn route).

Acquiring a local coach operator to bring more services under direct council control and reduce reliance on expensive private contracts.