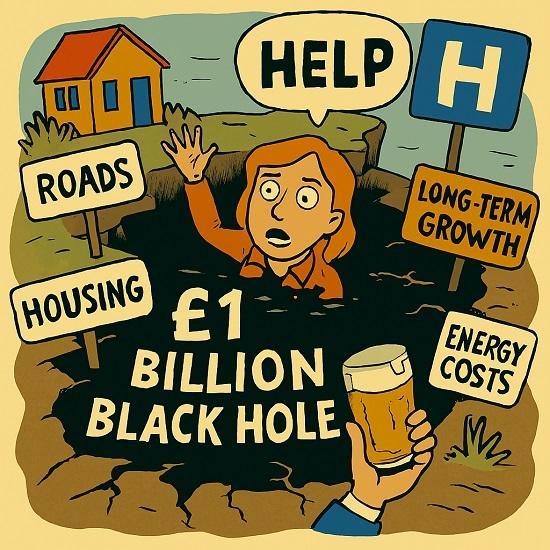

A Billion Pound Black Hole - Why Scotland's Next Budget Could Trigger a Capital Spending Crisis

11th January 2026

When Scotland's Finance Secretary stands up next week (Tuesday 13 January 2026) to deliver the Budget, the biggest danger may not be what is announced but what quietly disappears.

Behind the headlines on tax and public services lies a looming problem that threatens roads, housing, hospitals and long-term growth: Scotland's capital budget is under severe strain, and the numbers no longer add up.

At the heart of the issue is a widening gap between what the Scottish Government has promised to spend on infrastructure and what it can realistically afford.

Current plans point to capital commitments of just over £8 billion in the coming financial year, while available funding once borrowing limits and existing rules are factored in is closer to £7 billion. That leaves a shortfall approaching £1 billion, with no obvious or painless way to fill it.

Unlike day-to-day spending, capital budgets cannot be easily massaged. Scotland’s borrowing powers are tightly capped, and the large one-off revenues that helped plug gaps in recent years — such as income from offshore wind leasing — are no longer available at the same scale.

Meanwhile, inflation has eroded the real value of capital budgets, meaning that even flat cash settlements buy less concrete, steel and labour than they did just a few years ago.

The implications are stark. Capital spending underpins many of the projects that politicians like to champion: transport upgrades such as the A9 and A96, new social housing, hospital buildings, school estates and climate infrastructure.

A funding gap of this size all but guarantees that some schemes will be delayed, scaled back or quietly shelved. Even projects that survive may be stretched over longer timeframes, driving up costs further and reducing economic impact.

What makes the situation more worrying is that this is not a one-off problem. Medium-term forecasts suggest that capital budgets are set to fall in real terms for several years, while commitments continue to rise.

By the end of the decade, the cumulative gap could grow even larger unless policy changes or new funding sources emerge. In effect, Scotland risks drifting into a cycle where ambitious infrastructure plans are announced, only to be repeatedly postponed as reality bites.

This capital squeeze is also colliding with intense pressure on resource spending — the day-to-day costs of running public services. Public sector pay deals, health spending, social security commitments and demographic pressures are consuming ever more of the budget. When governments are forced to choose, it is often long-term investment that loses out to immediate demands, even though the economic damage shows up years later.

Politically, the danger is clear. Cutting capital spending undermines claims about boosting growth, tackling the housing crisis and delivering a just transition to net zero. Economically, it risks weakening productivity and slowing recovery at precisely the moment when Scotland needs investment most. And practically, it means communities waiting longer for improvements they were promised — or watching projects disappear altogether.

As next week’s Budget approaches, the question is not whether Scotland still plans to invest in infrastructure. It is how many projects can survive a system that is now structurally underfunded. Without hard decisions and greater transparency about what will be cut or delayed, the capital spending crisis risks becoming one of the defining — and most damaging — features of Scotland’s public finances.

The headline figures may look manageable. The reality beneath them is far more unsettling.

With the May 2026 election coming down the road fast what can an SNP government that has been in power for almost 20 years do to fend of the inevitable criticism that waving independence flags cannot conceal. The question now is which projects will be slowed or scrapped

Related Businesses

Related Articles